I’ve been obsessed with the sea for as long as I can remember. When I was a child I would regularly listen to the shipping forecast on the radio; and as a teenager I fell asleep most nights to the sound of rolling waves, courtesy of one of those soothing meditation-type cds that my mother had bought in a HMV sale. It is not, I think, difficult to understand my obsession, being, as I was, an especially unhappy young man who had frequent, intense fantasies about escaping my hometown, my life; and so the sea – alien, distant, mysterious and suggestive of freedom – was always likely to seem attractive to me. In this way, you could call me Ismail too.

“Whenever I find myself growing grim about the mouth; whenever it is a damp, drizzly November in my soul; whenever I find myself involuntarily pausing before coffin warehouses, and bringing up the rear of every funeral I meet; and especially whenever my hypos get such an upper hand of me, that it requires a strong moral principle to prevent me from deliberately stepping into the street, and methodically knocking people’s hats off – then, I account it high time to get to sea as soon as I can.”

As I plucked Moby Dick from the bookshelf it immediately struck me as smaller than I thought it would be, than I remembered it as being. Perhaps it is the way that people speak, or write, about it, as though it is this mammoth thing, THE white whale of white whales, that convinces you, dupes you, into thinking that it is some wrist-wrecking 900 pager. I think that readers fear the thing, tremble before it, and so it swells in size and girth, becomes more imposing than it actually is, in the same way that people who are scared of house-spiders see them as bigger than they are in reality. Or maybe it is simply the case that your own perspective changes as you age and grow, so that what was big to me at 14, when I first read the book, is now – with In Search of Lost Time, The Tale of Genji etc under my belt – a trifling thing.

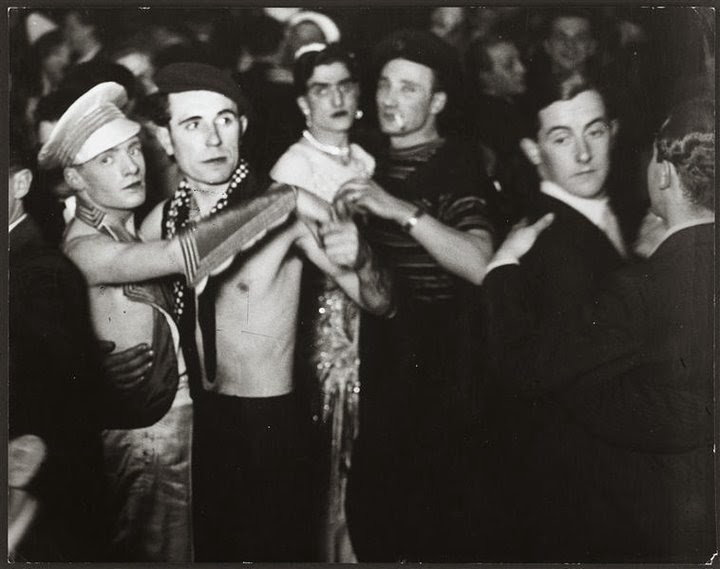

Despite the book’s reputation as being difficult and unwelcoming, the opening 150 or so pages are actually very easy to navigate, being conventionally plotted and, for the most part, light in tone. These pages focus on Ismail’s account of his and Queequeg’s friendship, and bring us to the point at which they board the Pequod. Moby Dick’s basic plot and central characters are so well-known that one cannot, therefore, approach the meeting of the two men in the same way as the original audience would; we will not be concerned about Ismail sharing a bed with Queequeg the cannibal and harpooneer, we do not see him as a danger or even as something alien, because he is so familiar to us. Yet, while some of the tension may have been sucked out of their initial encounter, the relationship remains one of the most interesting and surprising [not to mention homoerotic] in all literature.

“For all his tattooings he was on the whole a clean, comely looking cannibal. What’s all this fuss I have been making about, thought I to myself—the man’s a human being just as I am: he has just as much reason to fear me, as I have to be afraid of him. Better to sleep with a sober cannibal than a drunken Christian.”

Even taking into account what we are likely to know in advance, there’s a great sense of Melville bucking your expectations. One must remember that although Queequeg isn’t perceived as a danger by us, both he and Ismail are seamen and would-be whalers [that so manly, often brutish occupation], and the book was written in the 1800’s, and so one would not expect these two men to bond so quickly and intensely, especially as they are not able to communicate properly. Consider how, even now, people are often wary of strangers, and even warier of those who look and sound so different to themselves. Yes, it is easy to make jokes about a couple of dudes sleeping together [and Melville does nothing to discourage these jokes – having Ismail wake up with Queequeg’s arm thrown over him], but there is something so refreshing, even touching, about the tenderness they show towards each other.

Ultimately, the story of Ismail and Queequeg’s friendship is one of tolerance and understanding; so much so, in fact, that it is a positive example to us all. Not only does Ismail not treat his bunkmate as a dangerous savage, as something frightening and other, but he takes an active interest in him, his culture and his religion. There is a scene in the novel when Queequeg is engaged in worship, which involves a little doll, Yojo, and some wood shavings. Many of us would do roll his eyes or mock, But Ismail actually participates in the ritual. There is something almost child-like about this complete acceptance of another person’s differences, and the eagerness to learn about the things that are important to someone else, rather than judging harshly out of ignorance.

While all may seem tranquil, good-natured, and easy-going, during the opening of the novel, there are hints throughout of something darker stealing up on Ismail’s [and the reader’s] shoulder. There is, first of all, the innkeeper, Peter Coffin, whose name, in the Dickensian tradition, is clearly significant; there is the Inn sign that resembles, we’re told, a gallows; there is the gloomy sermon about Jonah and the whale, and so on. Most telling, however, is the episode involving Elijah, a strange, unnerving little man who appears to delight in teasing Ismail about the danger, or certain disaster, involved in sailing on the Pequod. Elijah, as I am sure most of you know, is the name of a man who features in the Bible as a prophet; indeed, the title of the chapter is The Prophet, and so one is left in little doubt that Melville’s Elijah knows his onions, so to speak.

The something darker that is being hinted at is, of course, Ahab, who makes his first appearance nearly two hundred pages into the book. This delay may be frustrating for impatient folk who want to get straight to the money shot, but keeping Ahab up his sleeve for so long is, I feel, one of Melville’s most successful moves, for, by the time he does show up, the boat is on the water, and so there is, for the crew, no backing out. This suggestion that the crew are essentially trapped on a ship with a madman, that they have, in a sense, been duped into becoming part of a madman’s dire crusade, gives the book a claustrophobic, tense atmosphere that is more usually found in straight horror narratives [something like The Shining, for example, trades upon a similar idea]. This is not to say that everyone is frantic and wringing their hands, but it is certainly the case that they all signed up under false pretences and are wary of Ahab.

As for the man himself, there has been so much spoken and written about the peg-legged captain that it seems almost pointless to rake over all that again, but one simply cannot ignore him. There is much in literature, as in life, that fails to live up to expectations, but Ahab isn’t one of them; he is everything that you want him to be: larger-than-life, enigmatic, tyrannical and unpredictable. Early in the novel, before he walks [or limps] onstage himself, he is described as a ‘ungodly, godlike man’ and I think that this is especially apt. One way to view Ahab’s obsession with the whale is as a manifestation of a god-complex, as a man trying to reign supreme over the natural world. I’ve long been interested in the psychology of men [it is usually, but not always men] who seek to conquer nature, by climbing large mountains or hunting tigers and so on. To my mind, what these people are trying to do is prove that they are better than, that they can bring to heel, the natural world, as though it has a consciousness that can acknowledge the defeat. It is, I believe, born out of a feeling of insignificance, or smallness. They look at this extraordinary, powerful force, and feel dwarfed by it, feel inferior at the side of it.

“He tasks me; he heaps me; I see in him outrageous strength, with an inscrutable malice sinewing it. That inscrutable thing is chiefly what I hate; and be the white whale agent, or be the white whale principal, I will wreak that hate upon him. Talk not to me of blasphemy, man; I’d strike the sun if it insulted me.”

On one occasion, Ahab speaks of the whale as a kind of wall, through which he must break, the meaning of which isn’t clear to me, but it does indicate that he doesn’t want to kill the creature purely out of revenge for having lost his leg to it. Many of his speeches are rants or strange quasi- mystical, philosophical soliloquies; at other times it is as though he were trying to inspire an army before entering into battle, and certainly one can see many parallels between the attitudes and action in the novel and war. Starbuck is the one character on board who openly, consistently, doubts his chief; indeed, he considers his monomania, vis-vis the beast, as a kind of dereliction of duty and his desire to avenge himself against it as ‘blasphemy.’ This blasphemy comment is interesting, because it seems to suggest, as mentioned in the previous paragraph, that there is a religious element to the chase, that Starbuck sees, as I myself do, Ahab as attempting to play God, or simply that by demonising the whale, by giving it conscious malice, he is putting it on the same level as a human being. As for the whale itself, I have heard, or read, it being described as a stand-in for many things, God being amongst them, but it is worth pointing out that Ismail cautions against allegory; the whale is, he writes, simply a whale. However, the Jeroboam’s Story chapter, featuring the prophet Gabriel, gives weight to the God theory. When the Jeroboam spies the white whale, Gabriel warns his shipmates not to go after it, believing it to be ‘the Shaker God incarnated,’ and then, when they come into contact with the Pequod, predicts that Ahab will die if he too attempts to kill it.

[P] MOVES AWAY FROM THE COMPUTER. HE LIGHTS A CIGARETTE AND STANDS WITH HIS BACK AGAINST A WALL

[Quietly, to himself] “Yea, tis true, tis true that ye sail upon tranquil waters for a time, but there be choppier seas to navigate. Look, look towards the middle distance: ahoy there, Cetology chapter! Aye, the sun doth go down, mates. Be not lulled unto sleep by that darkness, for ye will find thy craft capsiz’d while ye slumber. Do ye want to know about whales, say? Ask thyself: how much do ye want to know? Ye will know more’n ye ever thought ye’d need to know, before ye come into port. One on, one off! Aye, the narrative be reg’larly interrupted by chapters dedicat’d to the history of whaling, the nature and biology of whales…hold fast, mates, if ye be of little patience! Inexcusable? Unreadable? Aye, so some say. Yet, tis a book about whaling and whales, is it not? Pray, ask thyself: what was but Melville’s aim? I wager t’was not to bore thee. ‘Haps he thought ye whale-folk? Nay. Why, then? To instruct, to inform? Tis possible; no doubt he thought ye could profit by some background knowledge. But did ever an author care so much about his reader’s minds as to sabotage his own narrative? More likely he had a keener purpose in sight. Be it tempo, mates? A way of drawing out the tension? Or ‘haps tis contrast? Squalls and storms, madness and obsession, follow’d by stillness and calm, rationality and learning? Taking turns! Could be, could be…”

For those not familiar with Moby Dick, one of the most surprising elements is how experimental or idiosyncratic it is. Certainly, when I read it the first time I was not expecting Shakespearean soliloquies or chapters in the form of a play. Nor was I expecting quite so much of the book to be dedicated to short essays on the history and nature of whaling and whales. During this reread, I found myself in two minds about what some readers call the boring chapters. For the most part, I like the asides, the tangents, the almost encyclopedic approach; but I also think some of it could have been embedded in the narrative/story, that there are certain things that we should have seen the Pequod’s crew themselves doing or saying, rather than cutting away to a chapter that is entirely disconnected from the main storyline. Moreover, I think there are too many of these chapters in the middle section of the book. As I said, I mostly enjoyed them, but they do break up the story too frequently and, more significantly, for too long. For too long you are taken away from the Pequod, and so one is likely to forget what is happening on board. I’m also of the opinion that character development suffers due to Melville’s or Ismail’s preoccupation with understanding whales from every conceivable angle [it is interesting, as an aside, that one could call both Ismail and Ahab obsessed – one with knowledge or enlightenment and the other with destruction]; for example, early in the book one really feels as though you are getting to know Ismail and Queequeg, and one is given tantalising glimpses of Starbuck and Stubb’s characters, but this is almost entirely dropped when I would have liked it to be explored in more detail. Of course, the author could have done both, but he didn’t and one feels as though he chose one approach over the other.

All this is not to say that I don’t think these chapters serve a purpose. One can justify them in many ways: as a way of drawing out the tension of the chase, as a way of giving greater depth to the main storyline, etc. Ismail frequently explains a certain aspect of whaling and then says that this new knowledge will help one to understand something later in the book. In any case, no quibble or criticism I could make ought to be considered a serious one. Moby Dick belongs in the pantheon of the world’s greatest, most important, most profound, and most enjoyable, books. Really, no review can do justice to Melville’s extraordinary, immortal work. Everyone should read it at least once, even if, like a friend of mine, you have, to quote, ‘no fucking interest in fucking whales.’ Ah, see, it’s not really about whales. It is, as with all essential books, about you; it is about life.

“There are certain queer times and occasions in this strange mixed affair we call life when a man takes this whole universe for a vast practical joke, though the wit thereof he but dimly discerns, and more than suspects that the joke is at nobody’s expense but his own.”