Night times. Night man in the nightmare house.

The boy blew orange smoke from wheezing mouth.

The house didnotfalldown.

But he almost did.

*

Words brought me here. Or, I should say, my desire to avoid them. Except that they are, of course, unavoidable. I feel them like a heavy weight that bears down upon my head, such that every crude sound my lips make is painful to me. The knitting-circle nattering of my mind is even worse. And this? What I am doing now? This is the third wall that completes my triangular prison. My run down, but secure prison. I don’t want to write, but words come, regardless. Painful and inadequate words; but if not this, then the gurgle or the drone. I sometimes wonder if the only solution is death, but death is, I fear, a canny bastard. How can one even contemplate or summon it without words?

*

My life outside of work has become a kind of work, full of duties and responsibilities from which I long to escape. I’m always speaking banally to someone, with a contrived smile on my face; I’m always out in the evenings doing something, the purpose of which eludes me. During the week-days I sit at my work desk and dream, but not as I once did, not about walking out of the familiar door and down the familiar street and into the familiar building that I call home, when, finally, I can retreat into the familiar self. I now dream of unknown doors and streets and buildings and selves. These dreams, which for some would be meaningless without the nail of reality upon which they can hang, are superior to any of my external experiences, because they are at least mine; they are made from me, from my wild, painful yearnings.

*

I am starting to feel as though I no longer know what love is, or even whether it is anything at all. I was once so sure, so complaisantly sure, of its existence, its properties, its style. But it has now become elusive, like the shapes I think I can see when I close my eyes.

*

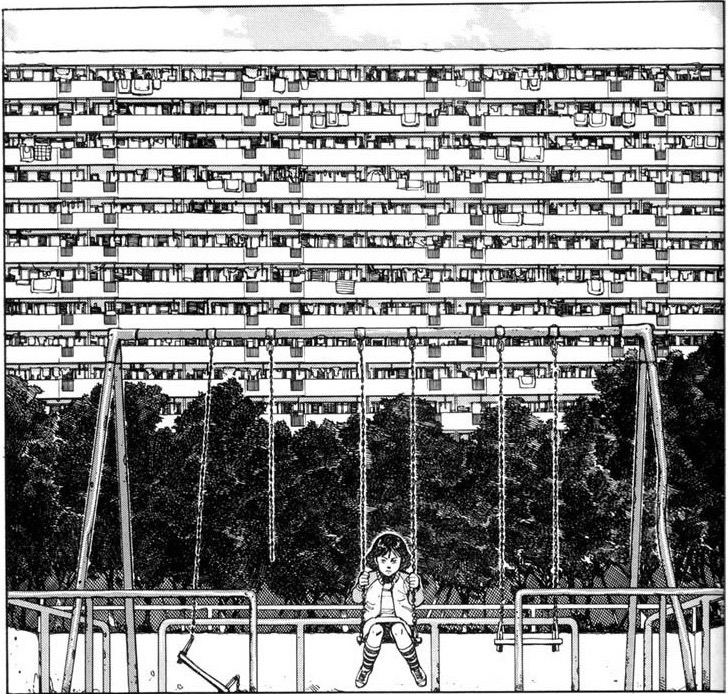

Following the separation of my parents I stayed for a while with my grandmother. I was around seven years old at the time. She lived in a flat, on a council estate in one of the city’s most deprived areas. The living room window looked out upon a run-down concrete playground, which never appeared to be in use, despite the large number of children in the surrounding tower-blocks. The old lady did not own a TV, most likely because she could not afford one, and so would each evening tell stories about strange happenings – involving ghosts mostly – which she insisted she had herself witnessed. Yet most terrifying was the story about her arrival in England. It was said that she had once been a member of an old aristocratic and wealthy Scottish family, but, for reasons that were unexplained, she was dispatched to a sanatorium while still in her teens. There she received electric shock therapy, and, upon her release, was subsequently disinherited and banished.

Whether any of that is true or not is, of course, debatable. I have, partly out of fear perhaps, but mostly in order to spare my mother any anguish or upset, never sought to verify what I was told. However, what is certain is that the unease I had felt upon entry into my grandmother’s home began to intensify to such an extent that it – the flat – was transformed, in my childish imagination, into a house of horrors, one that was large, unwelcoming, and labyrinthine. The ghosts, moreover, became real and malevolent and forever on the prowl. Indeed, according to my mother I began to have waking nightmares, visions in fact, of a man sitting on the end of my bed, who only I could see. I also, she claimed, started to sleepwalk, and could be found most nights at the front door attempting to leave.

*

For as long as I can remember I have wanted to be alone. I have, whenever possible, claimed space and time as my own. I have drawn circles around days in red ink.

Mine.

For years I pushed others away, so that I could satisfy myself; in private, inside myself; ‘I’ being the only person who could engage or pleasure me, I thought.

Could any man call himself my friend without feeling dishonest? Could any woman call herself my lover without pause? No. Never.

Many are they who have futilely hurled themselves against my tough and gnarly bark. Yet more have knocked politely and still walked away with scraped and bloody knuckles.

Now I am alone. I have cleared the driveway of my life as one would with snow in winter. Alone, but not alone; alone with my memories, for which, I’ve found, I have not eyelashes long enough nor strong enough.

To hold them, to bear their weight.

Alone with my memories, and the words I hope will distract me from them.

For years I used words. They came to me like desperate lovers. I wrote easily and often, and yet now, in my solitude, in these wide open spaces, they are much harder to find. The distances I cover exhaust me.

In solitude, I am reminded of the presence of others, and I wonder whether this is because I am not enough to satisfy myself.

How awful to long for oneself, only to discover that you are not that well-matched.

You seemed infinitely more alluring when all one had were stolen glances and moments. To become familiar with oneself is to become tired of oneself. Isn’t it terrible to discover that you are simply not that interesting, that you lack the strength to find in yourself the possibility of necessary surprises?

*

*

He emerged out of the swamp, to walk into the swamp, or so it seemed, leaving nothing but his dirty footprints, mud-stain, bog-stain, on carpets and floors. He was mad, or else everyone except him was mad. He remained calm – no, sullen – in the face of that madness, and threw everyone off. Some doubted his madness and believed in their own. He came looking, as others came looking after, for him. He found nothing, as they found nothing; for there is nothing. He circled nothing, circled empty space, and everyone was hypnotised by that circling, so that they didn’t notice how they’d been pulled into the circle itself, and how the circle expanded until it became a wrecking ball.

*

With concentrated thought, the boy tried to drown out the midnight drone, which itself was drowning out the scuttling of the night man as he ranged about the room.

Reflexively, he put his hand in his pocket.

He rummaged around, and brought up air.

*

He had placed his hand high up her thigh. She had expected this, or something like it. In fact, she had braced herself for more; but it had not materialised. He had come so far and then retreated, like a housecat nosing a gap in a window only to be scared off by the cold. She had braced herself, but wanted more. It was expected, and therefore necessary. Her disappointment made her stare. Her eyes were like polished snooker balls; the only thing he could see in them was his own sad reflection.

*

How strange that certain niceties and politenesses cannot be shaken off, how one maintains certain behaviours even though there is no one around to appreciate them.

*

He and a brother caught out in snow like many were caught, that day. Intense snow, soft and heavy like a pile of old blankets. Too hazardous for transport, all were warned by radio and TV to stay indoors. Except those already out, unable now to heed it. Almost equidistant from their father’s and mother’s houses, they had a choice. One or other, and walk. They chose mother, like they’d chosen once before. Felt like they mashed through that snow forever. Bodies forward, into wind and falling flakes. Edging along beside another road, in line with those also stranded. Sometimes he’d shout motivation into the snow, to a brother fallen down. Of course they made it, in their own time. After dark, a mother meeting them outside their home. Hot tea and sloppy affection, inside. Later, a story to speak on with everyone except his brother. Ashamed, perhaps. It was almost as though they’d shared a bed, not some snowy hours.

*

Somehow night had fallen, not with the giddiness of a drunken fool, but with the solemn slowness of a weary working man getting into bed at the end of a long shift. In the last pub, music blared and the lights flashed like cat claws. ‘You haven’t flirted with me,’ she said. That had been her invitation. ‘I have,’ he lied, ‘but maybe I haven’t been obvious enough about it.’ They had reached an understanding, and so she smiled and reapplied her buttery lipstick.

*

A gentle sadness. A mournfulness…for something, for what? I don’t know. For hope, for encouragement. A universal sorrow. I have always carried it in the pit of my stomach, always felt it, at least to some degree, but over the last two years it has grown, ever bigger, like a tumour.

*

The little girl walked away, up the hill, as though it was the easiest thing in the world. As he watched her climb, the sun dropped behind a bank of clouds and the air lost its softness.

*

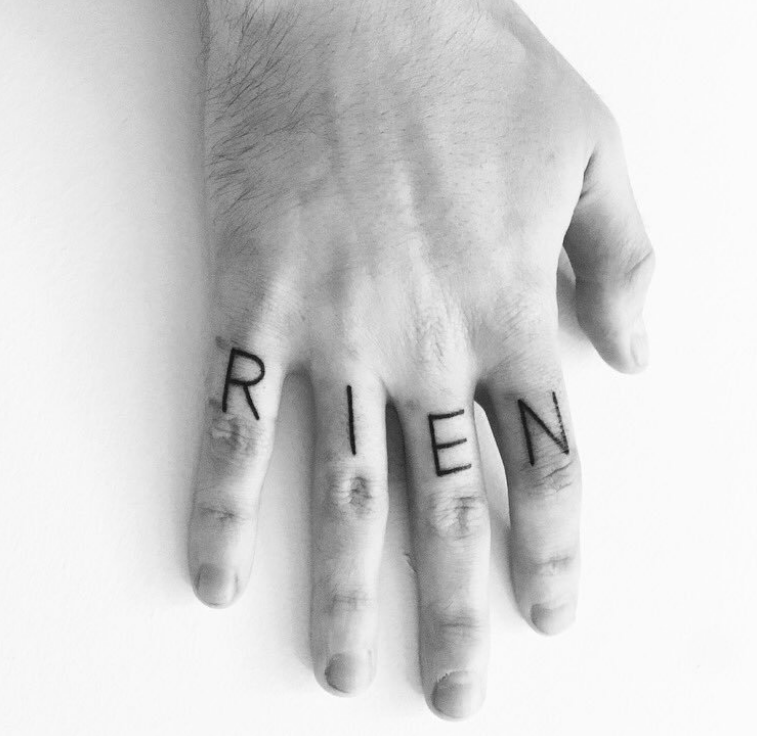

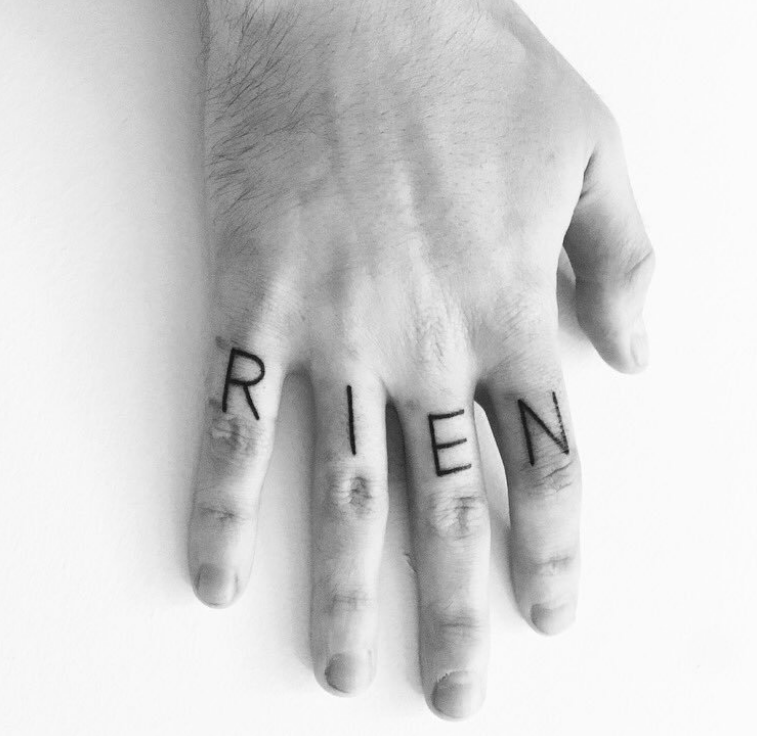

Rien. Nothing. I have the word tattooed across my fingers. Not to remind myself, because I never forget. That which awaits me? No, because there will be no me to experience it. It will be the absence of me. Nothing. The absence of all things. Including me. The void. I never forget, although it is impossible to contemplate it. For thinking is always targeted towards something. Everything we do, every aspect of our existence, is targeted. Even when we believe that we are not doing anything. That is simply a lie we tell ourselves. We are always doing something. We live with the idea of the void, not the reality of it. There is no reality. It is nothing. Not even the word with which we attempt to pin it down. Does anyone understand me? I am scared of this phantom blackness. Less than a shadow, than the wind. Less than the stillness, the silence. It is the absence of shadows, of wind, of stillness, of silence. Rien.

*

The night man laughed and drummed his slender web-spinning fingers on the boy’s skull.

*

It was three years ago that my grandfather walked onto the blade of the sword that old age had, for some time, been holding out to him. If we – his family – were honest with ourselves, we would have had to admit to feeling relieved. None of us had known what to do with him, before death had intervened and took control of the situation, with the great authority that only it is capable of. His behaviour had been increasingly erratic, like that of a young bird learning its trade. Sometimes his mental processes were graceful, even though impossible to follow; at others, reality impinged upon his flights, causing him to stumble. He was a once tough and capable man, who had been reduced to a curio; and I sometimes wondered if, or how often, he was aware of his own failings and, worse still, ours.

*

At the bottom of the hill he hesitated, pulling off his jacket and taking out his cigarettes as though he was stalling for time. It was Autumn, and the cool air crept over him like a lengthening shadow.

*

The day he came back it rained buckets, not as portent, no, but to show that this city would not raise an eyebrow and would not be diverted from its own normal course due to the arrival, or return, of such as him. No, he wasn’t in control of the weather, at least. Or if he was he’d brought on the rain five years earlier, in leaving, rain like tears of relief, like my own tears that day. So he came back, and so it rained; came back like from the dead, bringing death. He’d tried to be better, to be clever, and found that he was worse and more stupid than anyone here, these people who he had rejected, had attempted to leave behind.

*

Old mother with a collection of cats. Gave her something to survive. Her cats, like canaries. In that deadly house.

He’d wished for God, all his life. Prayed for Him, not at Him. With fierce desire wanted God, like a lover, so he need not be always alone. Playing hide and seek with himself.

*

– Are you good at climbing?

– Yeah, of course.

– You ever fall?

– All the time.

– I thought you were good at climbing?

– I’m good at falling too.

*

They come without being called, dog-nosing the air as though they sense a hard surface upon which they can lean or dash their heads. They claw at my heart, like a dog that has been put out for the night, with tales of infidelity, premature ejaculation, and a knife to the throat. And I sit impassively, sometimes sullenly, saying things like: ‘love means swallowing your pride and not allowing the bitter taste to show on your face.’ Do they believe that I can help them because I was born lost? Born lost, yes, but therefore never having known defeat. For them it is a new feeling, a new state of being, and that is why they are wild, why they writhe and howl in its strong arms.

*

How beautiful the world’s hands are, but how dirty its fingernails.

*

The world is collapsing under the weight of its own faeces…

How many times have I expressed this thought? In those exact words, in fact? The world…the world…I am tired of it. Let it collapse. Let me be at the bottom, the very bottom. Let me take the full weight upon my chest.

*

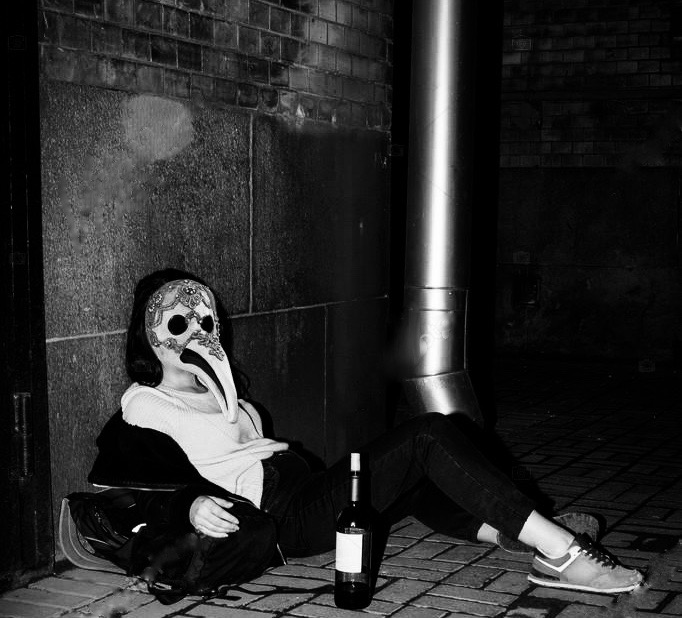

Over the last twelve months I have become familiar with the night. I have been turned out, with increasing regularity, to flit between darkness and artificial light with erratic, moth-like movements. I have become part of the once-mysterious nocturnal world that previously I only dimly perceived through my bedroom window or through the filter of sleep. Shouts and chants. Screams and laughter. Now it is all at my shoulder as I stop to lift heavy kisses to my lips on street corners.

*

There was a while when he looked as though he might outrun his own nature, when he began to build and fortify the fence; his brother acted as his press officer then, and poured eagerly into my ear reports of his progress abroad, as though he was Achilles taking Troy; with the arrogance of Achilles, no doubt, and the preening of Paris. He prospered; aye, he prospered in that interim time, before he was blown back here as though by Aeolus’ winds. And, if you believed him, what greeted him as he stepped off the train was a multitude of miseries, like a welcoming party or homecoming guard of honour.

*

*

To breach the surface of my unhappiness.

*

At the age of twenty two I quit my job, a good job, a promising career, and moved, with nothing, to London. I took a new name and lived a new life for twelve months. There are people still now who know me as that person. In their memories, I mean. That man continues to live, to be, in their memories. Two people. He and I; and I suspect he is having the better of it. Younger than I, fitter, more handsome.

*

My father is worried about Devil-dog. He has been out of intensive care, and a coma, for two days. Devil-dog! he shouts and points from the chair by his hospital bed. I’m not sure if he is pointing at me, but it appears so. Before his illness, I barely knew him; I hardly ever thought about him. It is only in this vulnerable state that his existence has become a thing, a fact, for me. Devil-dog, he shouts, and I think that he may be pointing at one of the tattoos on my arm. Or at least I hope so. Before his illness, my father was almost invisible to me; but now that he is on my mind, now that I see him at last, I realise how difficult his life has likely been. A man so meek and undemanding, so out of place and out of time, that the world – our world – must have been bewildering to him. Not once have I seen him do anything wrong; but then I never saw him do anything at all until now. It seems as though he had to lose his mind in order to impose himself, to speak up. Devil-dog! he shouts again, his frail arm extended and scanning the room; and suddenly I’m convinced that he’s passing judgement; on me, on all of us.

*

Perhaps in the sphere of reality, with all its flaws and faults, its awkwardnesses and disappointments, I could shed some of the layers of my love.

*

The longer I live the more I seem surrounded by people who are in the process of losing themselves. When I was a child I was scared; and everything connected to that fear seemed permanent. From my late teens onwards my life moved into different territory, one that resembled a graveyard but which was actually a kind of halfway house. Everyone drifting, moving out of my reach, like I am a cat trying to catch a light-spot on a wall that shifts each time I pounce. People like Tom, who I tried to help, but only ever in small scale ways that involved taking him for a drink, hoping he’d see in that gesture some kind of empathy, or assurance, because I was more afraid of facing his problems than he was. And then one day he was gone. He was no longer losing, he’d lost.

*

Our arrangement was that we wouldn’t talk at all, that as she entered my flat she would go immediately down on her knees without a word being exchanged between us. This was her fantasy. Throughout our communication, in the days leading up to her arrival, she always brought it back to this: don’t speak. She wanted to be treated like a whore. However, afterwards, after climax, once her mind had cleared, it became apparent that she was beginning to regret it. I have never done anything like this before, she said, in an attempt to excuse, or apologise for, her behaviour. Guilt and shame were working their insidious conjuring trick, transforming an event that was morally neutral into something bad, something negative, something wrong. What had been a pleasurable experience was already becoming that which she could not allow herself to contemplate or acknowledge. Yet, while she doubted and judged herself, I admired her. She had not only dared to dream, but dared to bring that dream to fruition.

*

For years I didn’t see it, even though I was present as my mother plotted her strange course to lands known only to herself. In the forest of childhood, truths are obscured. I was alone, deep within that forest, interpreting gestures observed through the gaps between close-standing trees.

I remember once inexpertly drawing the curtains together and she – my mad mother – strode into the room, as though she had sensed an impropriety and needed immediately to address it, her anger already dashing against the frail structure of her body. Without acknowledging my presence she tore at the curtains, almost pulling them to the ground. She shouted wild threats and lamentations into the air, her eyes vacant as she entered her own forest, chasing her madness like a cat would its tail.

*

This is not a love story. It was once, but my relationship with books has soured. Reading is, these days, like swallowing a cheap broth, one that contains the occasional scrap of meat, but which is, for the most part, thin, watery and bitter. Yet as a child I would avoid school and every day take myself to the local library. I would stand before the shelves in awe, almost afraid to touch, as I was so unused to things offering themselves to me. The rows seemed endless, unconquerable; and yet I perhaps now own more books than that library ever contained. I own so many; too many. But really they own me, and they oppress me. What was once my passion has become my prison.

*

For the first time he became aware that the room was empty, apart from the night man and the vulture; although the vulture, if truth be told, was asleep.

*

He circled nothing, I tell you, while our city burned. While everything seethed and writhed he looked on blank and calm, with sullen bewilderment, even while his self-created hell swallowed him up, while the demons and the possessed, for which he was responsible, ate him, and his kin, alive. And it was his choice; he came home, mark that. He came here: the place, I am under no illusion, he abhorred and had been so intent on leaving permanently behind, dismissing forever from his mind. The north, this city, yes, that too, but more than anything: home, or not-home. Aye, he chose to come not-home, and yet quite shuddered at the prospect, no doubt, and, once here, continued to shudder and wince and, in private perhaps, claw at his face and curse the curse he undoubtedly felt he was under; except he was the curse, of course.

*

I had felt, throughout the year, an intensifying fear, an increasing discomfort, a kind of claustrophobia, as though something terrible, something unavoidable, perhaps even fatal, was closing in on me.

One day, this feeling reached an apex, and drove me out of the house around midnight, with no plan or direction in mind. However, once outside a strange sort of calm came over me. The streets were clear, the sky starless; the cool air was like clean linen against my skin. Then, out the corner of my eye, I spotted a spider, suspended on its web; a black jewel in the centre of an ornate crown. I walked over to it, expecting to experience the usual grotesque fascination, the instinctive desire to crush, and yet, as absurd as it sounds, I was moved.

*

His shadow followed him home. Once inside, it retired to its own room and locked the door.

*

One stumbles around in the dark; hands groping, grasping at air, but occasionally slithering over something unidentifiable and unpleasant to the touch; eyes trained on the darkness, which is uniform, but in which, perhaps as a trick of the brain, one sometimes sees vague shapes.

The men, if they are men, do not know where they are going, only that they must go. No. Only that they are going.

*

They often come to me from different towns or cities. I meet them at the train station, and on each occasion, as we exit, and start the climb towards one of the bars in the city centre, I turn my head and draw their attention to the Park Hill housing estate. I know I shouldn’t do it, but I do. The woman is not the same but this scene is; repeated I don’t know how many times now. Look, I say, and they look. And then I begin my explanation, which, by this stage, is almost scripted; and I’m boring them, I know; and I’m boring myself; but I can’t help it, as I am intensely moved. I didn’t grow up in Park Hill, but it was a place just like it; hard, raw and grey. It’s pretty ugly, they say, or something of that sort. I don’t tell them that I feel ugly too, for this sort of thing formed me. I too am hard, grey concrete. For a while they stopped buses going up there, to the estate where I lived, because children would throw bricks at them. Where did they get such a supply of bricks? Were they stolen from the tower blocks themselves? In my mind I see little gutter kids sitting in the dirt, carefully removing bricks from the base of tall buildings. And in the next moment I see them toppling, in a perfectly choreographed, Twin Towers-like collapse.

*

I had received no word from him for five years, except through the agency of his brother, would never have heard otherwise. He had become a myth to me, some strange creature far removed from my experience of the world, who existed only in his brother’s fairytales and was therefore of no importance to me except to serve as some cautionary parable. So why did he come back when to come back was so objectionable to him? Because, for all his so-called intelligence and maturity, he couldn’t smell crazy cunt even when it was under his nose, that’s why; or, because, like most of his sex, he couldn’t turn up his nose at any cunt, no matter how clearly crazy.

*

My mother is an ill woman. Her brain is swollen with fantastical scenarios and characters; it is like a crowded prison, a prison she has been tasked with running but over which she does not have complete control. It is only at some remove, both in age and distance, that I have been able to recognise the power and range of her fevered imagination, her theatrical genius.

*

Suddenly there were women. I felt as though I had given birth to them, had created them myself, in my bedroom, under the covers. I had created them, then cast them far and wide; and now I sought to gather them up, to reclaim them so as to use them in private.

*

He hushed his heart, which, for as long as he could remember, had made a sound like the click of fingernail against fingernail.

*

Bodies crushed under avalanches of snow; hardy men torn apart by a substance as soft as tissue paper; babies blue, and harder than stone, ripping through the air like bullets. I have seen so many things. Awful things. They call it the end of the world. But this is not the end, this is still something. The end will be a relief. The end, the end. I’m fooling myself. There is no end. I am the cockroach.

*

It was the cowering spider that did it. I spied it crawling across the bedroom wall one afternoon. It was fairly small, but still had a grotesque bulb-arse, the kind that, when I had dispatched the others, had exploded under the weight of the shoe set aside for the purpose of killing. I immediately ran for this shoe, which had the dried remains of numerous arachnids caked to the sole. But I paid that no mind; I couldn’t afford to. Who worries about the carcasses of dead spiders when there is a live one crawling, blithely, across your wall? So, I clutched the shoe and pulled a chair over, for the thing was pretty high up and I didn’t want to overstretch and miss it and have it fall on my face, or even the floor, because falling spiders are my biggest fear, are what you might call the ultimate nightmare. I positioned the chair close to the wall, a little to the left of the spider, in case it should fall, and climbed up, my hand resting on the wall for support.

It was at this point, I would swear it hand-on-bible, that the spider cowered. Perhaps it had seen me, sensed me, or felt a vibration. I don’t know. But it pulled in its legs. It tried to make itself as small as possible. And that was it; the jig was up. There was no way could I kill it. In fact, I started to feel a kind of tenderness towards it. I named it; I watched out for it every day. I spared the spider because I saw in its behaviour some form of recognition of me, of my power, and this made me benevolent. Yet, more importantly, in that brief moment of silent communication between us, I also recognised the spider, and, consequently, it stopped being revolting to me. It was no longer some alien, unfeeling, creature; something entirely ‘other’, and therefore beyond my understanding; and so a relationship had been created between it and I.

*

It is at the end of a relationship that the most revealing statements are made. It is as though it is only when there is no hope of resolving the issues, of moving forward together, that people are able or willing to honestly disclose their feelings.

*

Of course, that’s not how it was told, first to the brother, then, like flotsam moving on the currents of a river, from him to me. No, it was much more poetically put; it was, to hear it from my youngest, who’d had it from the lying lips of his brother, a veritable Greek tragedy, which cast him (my eldest son) as an unfortunate Agamemnon, and me and the north as Aegisthus and Clytemnestra. But it took so little reading between the lines to see the truth; strip away the bombast, the melodrama, and there is my naked son, cowering and cunt-compromised. That he would not have had it that way doesn’t make it any less so. No. As he, in his severe self-pity, would have it he who never experienced any stability or normality – in his childhood situation, by way of his mother – subconsciously sabotaged himself. Ah, see, it was his malevolent mother who unbuttoned his flies and whipped out his perky prick and burrowed it deep in some slut’s slit – against his will, mark that – and brought him low.

*

Resuscitate your love, and in doing so make it immortal.

*

It had been announced at the beginning of the flight. There would likely be turbulence. The woman next to me had started crying before we were even in the air, as though she had been granted a vision, a premonition, of her death. Ordinarily I would have closed my eyes and tried to sleep, but I found myself fascinated by her reaction. When the plane shuddered, as though breaching a hard surface, her panic intensified and her sobbing reached the point of hysteria. It felt as though she was controlling the rocking plane and preparing to bring it down, that she was passing a death sentence on us all. She pressed her face into her hands and I wondered if she saw in the darkness the aircraft colliding with the earth, married with the earth, the cabin now a tunnel of fire and smoke. The more I thought about it the more I saw it too, the more I wished for it almost, such that I felt that she and I were somehow joined together in this vision, like the plane and the earth, our mangled bodies wrapped around each other as in a desperate act of copulation.

*

Prague. Praha. City of a Hundred Spires. I have left so much of myself there. At a bus stop in I.P. Pavlova with Daria. On the Vltava river with Shazir. With Eliška in Old Town Square. There are traces of me all over the city, like the mucus trail of a snail. Vyšehrad, Karlův most, Riegrovy Sady, Liliová. I have left so much of myself that I am not sure what exactly I have brought home. Except memories and longing. On the day of my return, the most recent return, I had a panic attack in the airport lounge, brought on by the sight of the plane that was to take me away. I felt as though I was being abducted, and I knew that all my captor would leave me with would be memories and longing.

*

I am still aware of it – my home city – creeping around, spider-like, in the corners of my mind.

*

I make these notes not in order to bring clarity to my thoughts and feelings and existence but as a kind of exorcism. I write as a means of relieving myself of a burden and to bring a semblance of peace and order to my soul.

*

Being alone like this, I find that I do not think better, but much, much worse.

*

I arrived by bus around midday, and I stood at the bottom of the hill, gazing up at the gloomy council estate in which I had spent so many unhappy years, and something unexpected happened: although I had come to say goodbye I actually felt as though I was reacquainting myself with an old, much-missed friend. How peculiar nostalgia is; it is like an amiable old cleaning lady who is able to remove the most stubborn, unpleasant stains.

*

On no more. On ground. In ground. Then done.

*

I plod through life in a disgraceful manner. I approach every day as though it were a Sunday afternoon in midsummer. So many times I have been encouraged to grab the tiger by the tail, and I agree that it would be in my best interests, and yet I never do. Instead, I gently rub its nose and admire its whiskers. In this way, many opportunities have passed me by, and I have watched them, sleepy-eyed, as though I was sitting on a warm and pleasant riverbank, and they were slow-moving sailing boats.

*

Poor, exhausted words; let them sleep, for they are over-taxed.

*

He sabotaged himself, we are to believe, because stability and comfort and loving-goodness made him panic, not having ever had any from his mother, nor the north; we, the north and me, sowed these seeds of self-destruction in my sad and sorry son, he merely, unwittingly, acted out the script we had written. So that he lost his lover, and his slut, and hobbled not-home with his trousers round his ankles. But he was not contrite. Sullen, aye, but contrite? No. To look at him, you’d not think he had taken all, had endured all, that a human heart could take and endure, which is how his brother had told it, the impression, in his epic re-telling, he had given of this courageous, ill-fated man, a man haunted by hopelessness and fallibility and, not ego, but, rather, the sins of his Machiavellian mother; a man who had stared into the depths of his bruised soul and found lurking there, no, nimbly moving from tree to tree, doing its best to hide, with only its head peering occasionally around the trunks of those close-standing trees, the evil gargoyle image of his mother.

*

Funny how, years later, I can still picture that one pose, how everything else has fallen away – all the bitterness, the arguments, the boredom – and I am left with that. I didn’t even see it first hand, I saw only her reflection in the surface of the mirror. I was sitting on her bed, and she, with her back to me, was grabbing at her short hair and pouting at herself; and I don’t know, I can’t recall, if I even found it beautiful at the time, but, after the break-up, this probably unreliable memory became, for a short while, an obsession, and the standard against which I judged all other women.

*

Increasingly the shark haunts my mind like it haunts the sea, silently slicing through the darkness. It is a ghoul, shaped like a knife-blade. It is swift and agile madness, with the skin of an elephant and teeth like the sharpest shards of glass. How feeble, how ungainly man seems when compared to this creature, how unlike a God.

*

Yet how well he kept it hidden, this anguish. Docile? No. Say, sullen; but more than anything: closed. At least to his gargoyle mother, who, so his little brother said, he cast as something like the Iago of the piece, who was off-stage, yes, but still whispering hate into his ear; and yet it was he who hated, not me. No, I claim no hate; suspicion, yes, and fear, but not hate. He hated, in that passive aggressive manner so particular to him, by being in my presence so sullenly unresponsive, so unanimated, while pouring pestilence into the ear of his brother; he Iago, ironically. And I, yes, deformed, disfigured, and deathless, but not hateful, although I have every reason to be. What reason, has he? He who left without a word, and lived without a word for five years. He who sought his glory abroad, who puffed himself up, when he thought victory assured, and looked down upon the mother, and the place, he’d used as the motivation to better himself.

*

Memories are like unmastered dogs, they come when they’re ready and not when they are called.

*

A few years ago I was outside, walking along, and a large black and white bird – of a type I had never seen before – fell out of a tree and onto the pavement. Straight down. No flutter of wings. No noise, except the dull thud of its body hitting the concrete. It was unhurt, however. I raised my eyebrows and carried on walking. Coming towards me was a young woman with a pushchair. The pushchair was empty as the child was by her side. As they passed me they noticed the bird. Poor thing. I turned around. They had stopped and, fearing for the bird’s safety, were trying to usher it off the pavement and onto some grass. Arms outstretched. Both mother and child. Chik. Tsk. Here. No. There. Unfortunately, the bird did not understand. It ran away from the outstretched arms, the welcoming, protective embrace. And into the road. And under the wheels of a slow-moving car. Crunch. I’d never heard anything like it. Drawn out…cruuuuuunnnnnch. How it is. How it will be. Dear God.

*

Look who just walked in, my friend said. I tried not to look. This is why I don’t drink around here anymore, I thought to myself. My friend nudged me. Do you remember that guy? Of course I did. It was impossible to forget. My friend walked over to the bar and introduced himself. Are you him?, I heard him say. I might be, the old man replied with a sly grin. I thought my friend was going to buy him a drink, but thankfully he didn’t. The story goes that the police had been trying to put him away for years and eventually they did it. They got him for what must have been fifteen-to-twenty, and now he was out. I don’t know what they pinned on him, and I don’t want to know. Once, or so legend says, he was summoned to take part in a retaliatory raid on a local pub full of rival gang members. His one instruction was not to stab anyone. Beat them up badly, yes, but don’t stab. You got that? Sure, man, sure. Of course, he didn’t listen. As the members of the rival gang fled the pub he stuck a knife in the first three he saw.

You’re not having another? No, I said, eyeing the dregs of my drink. My friend had returned to our table and now I wanted to leave, to flee with the same kind of urgency I felt when I was boy. Only then it was a whole city, a whole life I wanted to escape, and this time it was just a sad old man and a sad old pub and a sad old situation. Are you alright? It was a joke. I almost smiled. No one ever asked you that back then. Are you ok? Can you handle this? Do you need any help? I didn’t look like a tough kid. And I wasn’t; not physically, at least; but I was desperate and crazy, and that is sometimes worse. The city did that to you; or our small, wretched part of it, anyway. Do you remember when we were kids?, my friend said, with a kind of smug complacency. He had allowed nostalgia to transform his memories into an heroic narrative, one worth reminiscing over, but I hadn’t. The pain, the blood, the fear; the heavy, sour smell of hopelessness in the air. Yeah, I remember.

*

I experience life as though I am behind glass, as though some barrier exists between me and the world that obscures, muffles, and distorts it.

*

Something happens when I drink alcohol, some kind of mechanism in my brain gives way; and so the writhing mass of thoughts that harangue me when sober, the near unbearable, seemingly limitless, and constantly overlapping, multitude of thoughts, that I liken to a big tub of live eels, are given expression.

*

In times of unhappiness my mind rummages around in the past for poignant or painful memories, as though seeking brotherhood or solidarity.

*

Marc was an ugly, ginger-haired boy who had been in my class at school. We had no common interests, but had somehow managed to become friends, in the way that children form friendships by stumbling blindly, mindlessly into them. One day, while still at school, he had given me a squirrel’s tail as a present. He had shot the creature himself and thought I would appreciate the gift. I hadn’t the heart to tell him that what he had done disgusted me.

I hadn’t seen Marc since leaving school, hadn’t, in truth, really given him that much thought. Until one day I spotted him outside the entrance to my college. I have no knowledge of why he was there, because I did not ask him, although I knew that he was not a fellow student. I do not know, either, how he felt upon seeing me, whether it caused him distress, as it did me. Yet it was not the encroaching of one world – my school-life and my childhood – upon another – my college-life and my adolescence – that distressed me, although I cannot say that was pleasurable, it was his missing tooth, one at the very front of his mouth.

Marc’s missing tooth, I understand now, although I didn’t understand it then, was significant only in so much as it was missing. In other words, it was the fact that it was once there, that I had seen it, which meant that I felt its absence so strongly. As embarrassing as it is, it made me sad to see that space in his upper gum; and I have lived with a kind of sadness ever since, I have clung to it as though it was the breast of a stout motherly woman. Where is life taking him, that once tough little boy who had tried to win my affection? What else has he lost along the way?

*

She kissed in short bursts, like a small child. I found it both frustrating and sad. It was as though no one had ever kissed her properly, with feeling, and so she pecked at my face like a cautious bird.

*

What reason? Was it the realisation that the land he’d claimed, the spoils he’d claimed, weren’t ever really his? That what you steal does not ever truly belong to you, even if you never relinquish it? Someone should have told him: you are wretched with or without possessions, because you are you, regardless of your university education, your high-flying job or your pretty perky-titted partner, you cannot outrun yourself, even if you outrun your mother and the north. But they didn’t, or if they did he paid it no mind. And so, unwilling to blame himself – the real villain of the piece, mark that – he blamed the two things he’d so thoroughly rejected, the two things more removed from him than anything else, and did it convincingly.

*

I feel as though I am searching for someone, and for a place, for reasons I can’t quite articulate to myself, which have, in fact, never existed anywhere except in my imagination.

*

My career as a master criminal was short-lived. I was twelve or thirteen, and bored, bored with my life, with being poor, with having no prospects or anything to look forward to except the day when I could leave the place that I called home, where violence and misery stalked my heels like a pair of dark dogs. I had walked to Meadowhall, a large shopping centre that resembled a hellish doll’s house. I had no money, but didn’t really desire anything anyway. I simply wanted to be somewhere away from what I knew, where, to my immature mind, people were living differently. I took a turn around a bookshop, lifting books from the shelves; and then, without making any kind of conscious decision, I put one of them under my t-shirt and tucked it inside my jeans. I expected to be caught as I walked out, but I wasn’t.

I was more scared when I got outside, when I had got away with it, than I was in the act of stealing. I knew I had done something wrong, that it should not have played out like that, and that is why I went back. I realised afterwards that I wanted to be caught, that being caught was part of it. Something had to happen, of that I was sure. I wanted something important to happen to me, something momentous, to give my day some sort of meaning. So I went back in, and I came back out again. Another book. No one batted an eyelid. Three, four more times. Nothing. The situation had become absurd. I was untouchable, or so I felt. Why will no one acknowledge me? Am I really this insignificant? And then, eventually, they did notice me. I had become increasingly reckless; I made no effort to conceal what I was doing, and, in fact, could barely walk for all the books I had hidden on my person.

I was relieved when the security guard touched me on the shoulder. He wasn’t rough, he simply requested that I turn around and accompany him. He took me ‘in the back,’ behind the shop floor, and the police were called. Only I don’t think they were really the police. They didn’t have on uniforms and they don’t send out non-uniformed officers to deal with teenage shoplifters. It was a ruse, a way of scaring me straight. I was already straight, they didn’t get it. I wasn’t going to steal again. I had done it and had got what I wanted. The policemen drove me home. I sat in the back of the car swearing to myself. They threatened to arrest me. I smiled.

*

They think that I hate them. But it’s not true. In fact, I admire them. They look so happy, so relaxed. I don’t feel happy or relaxed; not in their company; not in any company. I cannot relate to people. Their preoccupations, their conversation. I can fake it, of course, and I do sometimes. With girlfriends mostly. I use them in order to fool myself into thinking I am not a hopeless case, and because their grace and beauty soothes me in the same way a cat’s does. Actually, it’s not correct to say that I always use them. Occasionally, my enthusiasm, my participation is genuine; occasionally I am engaged; but it’s rare. Most of the time I feel as though I exist behind glass. It’s hard to fake being-like-them consistently. It’s like trying to perform a complex dance routine when you have only learnt the first couple of steps. You might look as though you know what you’re doing initially, but soon you’re stood uncomfortably still and silent in the middle of a room.

*

He responded to the invitation, the demand, to speak or listen to the worn-out stretched-to-the-limit old woman with little enthusiasm. She, who was worn-out to the limit, beyond decaying, beyond death, beyond recognition, holed up in her worn-out house, shawled against the weather and shawled against the city, against people like him, black-shawled, forever black. Her room, even more than her house, was her feeble ‘no’, her croaked protest against all that she had seen, had suffered or thought she had suffered for the last fifty years. So why had he been invited into that weak thin-walled shell of a house of a room, stepping carefully? What had she for him, what to say to give to offer up to her son except a lamentation, a wail as thin as her walls, as black as her shawl her tongue?

*

Someone should have told him: the fence you erect around yourself and your new life, in order to keep your mother and the north out, is pointless when the real threat to yourself is the one who erected it. He fenced himself in, and, in doing so, frustrated and enraged his enemy (himself), because suddenly everything (except the mother, the place) outside, everything beyond the fence, became more important, more necessary, more tempting, more alluring; and so he burrowed deep in some slut’s slit in order to claw, to dig his way out of the trap he had set, the prison he had built for himself. Yes, stability may have made him anxious, may have made him panic, but not because he who had never experienced stability couldn’t cope with it, as he claimed via his brother, but because it was only when he’d agreed to forsake all others, to settle in one place, to every day accept responsibility, in private and in public, at home and at work, that he realised how little excitement there was in that.

*

Overhead, birds as big as cats circled slowly as though tired of the day.

*

It wasn’t a conscious decision. Reading is not my life’s passion, it is a symptom. Being drawn towards books is simply a way of drawing away from you, all of you. As a child I convinced myself that my environment was to blame, that of course I could not relate to those sorts of people, and yet I have long since left behind that environment, and those people, so what excuse do I have now? I still can’t consistently relate. To loved ones, occasional ones, anyone. Naively, I thought it would be different when I started relationships, relationships I entered into freely, with women I chose for myself. With women I like and who like me. For a while. I’m gloomy and difficult, yes, but I’m not an idiot. My choices are made rationally. For a while it was different. It is different. But the hole in which I hide isn’t big enough for two. Not long-term. It’s too cramped, and the books take up a lot of room. So they leave, and I feel relieved. For a while. Until I start to panic, because life, I think, cannot be lived in isolation, cannot be lived only amongst the dead.

*

I once misread ‘the intimate forms of address’ as ‘the infinite forms of sadness,’ and liked it much better.

*

*

As his mother readied herself, the boy sat watching with the quiet alertness of a suspicious animal that is not yet sure whether the rustling in the bushes is merely the wind or the approach of a genuine threat. She pulled on a dress, put jewels in her ears and made up her face. When she turned away from the mirror and sat down on the edge of the bed to slip on her heeled shoes the boy realised for the first time that women are not one, but many, depending on the circumstances, that women have a multitude of faces and bodies to choose from and that the choice is somehow related to the person who is going to be doing the looking.

The face and body he saw before him were brighter and more colourful and approachable than usual. Looking at his mother he felt a kind of yearning, a new and painful yearning, to touch and taste, and he experienced a strange embarrassment as though he knew that this yearning was inappropriate somehow.

*

I see the chaos around me as a ball of string to untangle.

*

So he burrowed deep, made a bid for freedom, with the only tool at his disposal; only, being a man, he didn’t actually want to escape, not completely, no, he simply wanted to be able to come and go as he pleased without consequences. And that may even have been possible had he been able to smell crazy cunt in front of his nose, but he could not, not until after he had had it and the slut had revolted, with the volatile, immolating, retributive fury of a crazy slut who has been treated like exactly what she is. Oh then he could smell it, certainly, when it was too late, when the whole infrastructure of his comfortable life had been torn down and set on fire.

*

Your life is an unmanageable and complex web of dreams and imaginings.

*

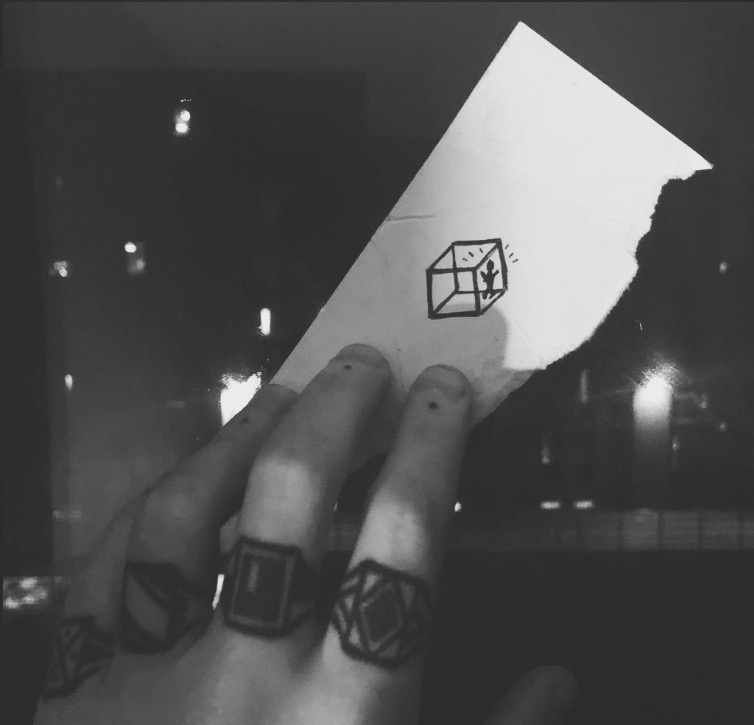

He had this idea. I don’t know how to explain it properly. He wasn’t anything to me, just some guy I’d see around, and, I don’t know, mess around with sometimes. If I saw him again, ok. If I didn’t, or if you told me I’d never see him again, then I’d have been fine with that too. He wasn’t all that keen either. I mean, I’ve had guys bugging me and bothering me, and ringing me up or trying to engineer meetings. He wasn’t anything like that at all. He never seemed particularly interested, though he was nice when we were together. Anyway, one time we were doing whatever it was we did. We’d bumped into each other and we went for a coffee. And that usually meant more than just coffee. I’m not explaining this very well. The important thing is that he told me something, that day. Or gave me something. Some kind of instruction. He gave an address, of sorts. Or directions. And a time and a date. The date was in the future. I said: what’s this? And he told me that he had an idea, which was probably stupid and doomed, but he couldn’t let it go. His idea was that everyone he’d ever spent time with, at least since the idea came to him, should meet, or come together, in one place at the same time, on a specific date in the future. Honestly, I thought he’d lost his mind. It made no sense to me whatsoever. He must have noticed, because he tried to make it clearer. He said: wherever you are in the world, whatever you’re doing, I’d like you to come to this place – and pointed at the piece of paper he’d written his instructions on – at that time and date. Why? I asked him. He told me that life made no sense to him, his life made no sense to him, and he wanted to see it, that it was the only way it would seem real to him, to see everyone he’d known all in the same place. He said he didn’t want to mingle and chat to everyone, that he would, when he imagined the event, stay back, probably out of sight, and just look at his life. I laughed. I said: you’re insane. And I meant it. I said: do you ask everyone? (I had trouble getting my head around it, that he was asking hundreds of people, more maybe, to stop what they’re doing and come to some appointed place years and years in the future, just to stand around and be looked at). Most people, he said. He told me he’d started out with the idea that it should be literally everyone, everyone he’d ever laid eyes on, but almost as soon as he’d had the idea he realised how impossible it was, especially as he didn’t intend to stop, or to give up on his idea, that he meant to keep asking more people, year after year, the number (assuming, for a moment, that everyone attended) would be unmanageably large. It was the only way to get the full story of his life, he said, but he wasn’t crazy and he knew it couldn’t work. But this can? I asked. Yes, he said. He said: look, I know not everyone will turn up. Why would they? But I hope some will, that enough will. I asked him if he were drunk or something. He said he wasn’t. He said: it’ll be like attending my own funeral, and everyone wants to attend their own funeral. I told him I’d try to make it. I said it was the best I could do, and he seemed satisfied and never mentioned it again, not for the rest of the day or any other time I bumped into him. But I found I couldn’t forget about it, even though initially it was just a crazy story to tell other people, to laugh about. But after a time I started to take it more seriously. The older I got and the more people I lost touch with over the years, the more I reminisced, the more I lived in my memories, the more sentimental I became, the more it started to make sense to me. I was living in The Hague, in Holland, around the time the event was meant to take place, and I could barely breathe all that week. I seriously considered getting on a plane and going, and even though I didn’t, and the time has passed now, I still regularly think about it. Did it happen? Was he there? Or was it just some extravagant, eccentric joke?

*

For someone who is so scared of death it is rather perverse, or certainly absurd, that I spend so much of my time amongst the dead.

*

So, as much as he abhorred the place, he returned, because only here could be find a sympathetic ear (his brother’s, not mine), someone naïve enough to believe his cowardly lies and embellish and spread them, someone who believed entirely in his heroism; he returned, not merely out of financial necessity, as he claimed, but for that, for a credible, gullible, audience; and for revenge, let’s not forget that. He sought revenge against his mother and this city, because only in seeking revenge could he fully convince himself and his audience that what he said and thought about his gargoyle mother and his (yes, his) city was true, that without the desire for revenge he would be revealed as a charlatan.

*

It occurs to me, while wandering through pointless daydreams, that someday the soft skin I once caressed will be shrivelled and sagging and old, and I am forced to acknowledge to myself that my own will be too, and that the desire to plant scandalous kisses upon that flesh will seem ridiculous, if it even exists within me at all; and that likewise, the desire to be kissed by me in that way will exist in fewer and fewer women.

*

When I was a child I would play a game which involved using a jar to catch bees. I’d shake the jar and then open the lid and run away from the infuriated insect. However, on one occasion I shook the jar, dropped it and ran, but the bee didn’t chase after me. Cautiously, I returned and peered through the glass. The bee was stationary inside, perhaps injured or confused or dead. I felt, at that moment, an intense sadness and shame.

*

We hadn’t even finished our first drinks. This is what I do now. I invite strangers back to my place. She invited herself, in fact. She thinks I have a cat. But the cat is dead. She doesn’t seem to notice. I guess she isn’t here for the cat. I’m wishing I had drank more, so I could feign impotence. She notices the books. It’s difficult not to notice the books. ‘Wow, you have a lot of books,’ she says. She wants me to show her the one I spoke about on the way home, which, I now realise, I mentioned in an effort to put her off. The disgusting one. She’s not unattractive, but I have done this too many times to find meaning in it. I’ll cover her in my scent, in my DNA, and then she’ll leave and never return. I collect these women now, in the same way I collected all those books, without ever really enjoying it. I’m surrounded on all sides by shaky towers. One day I’ll die under a book avalanche. ‘You must love reading,’ she says. I want to tell her I hate it. This, I think, with an imaginary sweeping gesture that encompasses her too, is not about love.

*

Have you ever had the feeling that you’re being followed and watched? Lean into the darkness and what do you see? The alley, the wardrobe, the space under the bed, the cracks in the walls – lean in close and what do you see? Maybe you’re being paranoid, for when you root around in the dark corners of your life there’s no one there. Still, you’d better clutch your keys, or quicken your step or pull the duvet over your head. There’s a knife in the kitchen which gives you peace of mind but which, you note to yourself, could equally be a murder weapon. I once had a stalker. Once, perhaps still. Who knows how good she is at the task she has given herself. Stalking like anything else is a skill one can develop. I would see her, fleetingly, although we had never met, in shops and on streets. I knew her from her photographs, in which she was naked and her face was turned away from the camera. Someone, if not her. Something, if not her. A powerful force dogging my heels that never fully reveals itself. I lay awake every night, cat-eyeing the dark corners of my life.

*

There it was: a grey hair; gesturing to me in an offensive manner. It was like staring at a crowd of people and suddenly spotting, deep in their midst, a child looking my way and insouciantly giving me the finger.

*

The nature of lodging is mysterious and disquieting. A lodger is a stranger, someone without a home of their own and, it seems, neither family nor friends upon whom they can depend. Yet they too are vulnerable, entering the home of a similarly strange person, whom they do not know and cannot completely trust.

I have felt like a lodger all my life.

*

To his (little) brother he was extraordinary, be it in victory or defeat; or not-defeat, never defeat, because even though he appeared to have been brought low, even though it looked like he had lost all, and had come back, and filled his (his brother’s) ear with melodramatic psychobabble dressed up as high tragedy, I’d say he (his gullible brother) saw not real defeat in it, but a temporary, even necessary, regrouping of mental forces, a mere episode, one small, yet still engrossing, segment of his (his elder brother’s) tapestry of war and ultimate victory. Aye, he was, I think, in his eyes a sort of Zeus, a powerful, and sometimes gloomy, god of sky and thunder; which makes me a kind of Cronus, a child-eater.

*

I didn’t initially suspect anything untoward; an unfortunate series of events is what I called it. I am not mad; or at least I was not. In a world where anything is possible, where an infinite number of things can happen at any time and in any sequence, a run of bad luck, especially for someone with such poor judgement, was unwelcome, of course, but did not strike me as unduly worrying or significant. Yet, as the disasters have shown no sign of abating, have in fact increased in frequency and seriousness, I am at the point of seeing a sinister hand in this, a plan, a vendetta. Whose hand? God’s? No, with my ego having been brought to heel by these catastrophes, I can no longer believe that there is anything in my wretched case that would interest a deity. But someone; something. Fate? Perhaps. A force, certainly; inexplicable, unseeable, unknowable, but felt.

*

My nose pressed against aquarium glass, watching ugly fish swim in unclean water.

*

A few days ago I became ill. I have a good immune system, but it failed me this time. Something got in, and it hated me. It started in the evening, when I realised I could stand, but I could not walk. Then thin water started to pour ceaselessly from my eyes and my nose. And I shook, my teeth rattling like a tin can full of coins.

The following day I found it difficult to remain conscious. I’d open my eyes and immediately they’d start to close again. In the one or two periods when I was awake, I found that people were attempting to communicate with me. My mobile phone lit up. My brother entered my room. I watched it all impassively. Nothing mattered to me, except heat. I glared at the radiator. It ignored me. In the midst of the demoralising cold and the illness, my consciousness had been reduced to some kind of Neanderthal state, whereby I was only dimly aware of myself as myself. I was no longer complex. I was basic. I was mentally rubbing two sticks together.

The cat must have sensed something. He would prowl around the bed, making horrible mewling sounds, before jumping on my chest and laying down. I was sure he was going to eat me, or suck what little life I had left out of me. If I shooed him off he would skulk away, only to return moments later, in the hope that I was now too weak to resist or defend myself.

*

There are no trapdoors, only doors upon which my diseased mind has imposed a sinister significance.

*

Imagine that someone has promised to give you a beautiful old watch. There is, however, a catch, or drawback, for the watch, you are told, does not work; there is some essential part of the mechanism missing. Sadly, you’re no expert on watches and their workings; in fact, you have no knowledge whatsoever on this subject. Moreover, the missing part is no longer available. Fixing it, then, is out of the question. Do you, in this situation, feel aggrieved, because the watch is not all that it could have been? Or are you happy to have it as it is, being of the opinion that you have gained, rather than been denied, because you cannot lose something that never was and could never be?

*

The perfect partner, the slut, the job, the swanky apartment: all were lost. And he a hero, still? Yes, it seemed so. His losses were heroic; when really it, the situation, could have, or should have, been, for him, for his little brother, like seeing his father bested in a physical confrontation. The scales ought to have fallen from his eyes, as he (his elder brother) fell. Yet, I’d say his admiration for him was never compromised, in fact he gained from his fall, which for him wasn’t a fall but a regrouping, a greater mystique, a quixotic gloss. Even the slut escaped the youngest’s ire, for she was necessary too, she was part of the fabric of his epic tapestry, the heroic narrative; she, with her madness, her looseness, her excoriating temper, was equally quixotic.

*

No matter how awful, how painful and degrading existence is I cannot forsake it. Not only that but, with a miser’s spirit, I actively cling to it.

*

It was early in the afternoon, around 12:30, as we left the museum and started the crossing. Straightaway, I noted a woman having her portrait drawn, a smile stretched grotesquely across her face as though it was intent on swallowing her. Further on, a spidery old man was playing an overly-large accordion, and what appeared to be circus performers were blithely strolling in the midday sun.

The walk along Karluv Most bridge appeared to be unending. My feet moved, but I felt as though I made no progress. Dogs, so many dogs, all the same breed, and all wearing scarves, passed by me at regular intervals. It was as though I was standing still, and they – the dogs – were going round in circles, were circling me, coming back around, time and time again. Where were they coming from? How could it be that ten or fifteen of the same breed had found themselves on the bridge that day? And why were they dressed so suavely? I have lost my mind, I suddenly thought to myself; then, gripping my friend’s arm, I asked him, straight-faced, with great seriousness: ‘You can see those dogs, can’t you?’

*

Only once have I been considered mad by the world at large. Yet it is, perversely, when I felt most sane. I sought advice from the doctor upon the urging of my intimates; and what did he say? Nothing. He cowered before my tears and my reason. I had stopped being able to laugh at life, to find absurd amusement in what Rene Daumal called ‘this monkey cage frenzy.’ I saw clearly that a conventional existence was terrifying, painful…impossible. I could no longer continue in the hapless, mindless manner I had become accustomed to. The doctor gave me a prescription. I later found out that it was for the kind of drug they give to patients in mental institutions, the most unruly patients, who are, to quote, ‘literally climbing the walls.’ He wanted to sedate me, to dupe me into again accepting what I had renounced, what I felt as though I had transcended.

*

My son never saw the slut, he never saw the lover neither; and wouldn’t have seen them even if he had stood in front of both, no, he would have seen the character, the part they had been given to play, the role they had been assigned. Believe it or not, my son saw no malice in his brother, no callousness; he exonerated him on the basis of the psychobabble he had been fed, while simultaneously elevating him to ever greater heroic heights in the epic narrative he was feeding himself. So, no, he saw not a flawed unfeeling man who had shlupped some slut out of boredom or vanity or that male need for distraction or novelty and then discarded her as though she was no more than what she was; he did not see an ignoble sordid soul who, although already attached, had pursued a crazy cunt, not yet knowing how crazy she was, and bedded her without bad conscience.

*

I’ve written about Tom before. He is, you might say, one of my recurring, minor characters. I use him, not without a seasoning of guilt, when required, which is to say when my thoughts are focussed on those who feel small, ill-at-ease, and unappealing. In any case, I don’t have to worry about him reading this, because these days he only exists within me, caught in the sticky web of my memories. Tom always considered himself ugly, rightly as it goes. A mess of curly hair, as though someone was building a bonfire on his head, was probably his best feature. I am not, of course, under the impression that I am a very handsome man, but I cannot, nevertheless, relate to those who, like my friend, are so self-conscious about their appearance that they hide themselves away, and run from life until all that is left of it is a small black dot in the distance.

*

There is no place for understanding now, for the goal of understanding is progress. And we are going nowhere, not even backwards. The only movement comes from the ice and the snow, that constantly shifting, vertical and horizontal, oppression. An arctic prison, built around a void.

*

You might argue that we impose meaning on the world, because otherwise it would be too overwhelming, too chaotic, too frightening. The world is bigger than us, more powerful; and therefore we try and bring it to heel. Yet, for me, it is an ordered world that is overwhelming; what is terrifying is relentless meaning.

*

I remember kites that would not fly and fish that would not bite.

I remember licking a blade of grass and showing my friends the bloody paper-cut.

I remember standing by the open window of the top-floor flat I lived in as a child,

My arm outstretched, dangling a chewed-on pencil over the edge,

And how that was the scariest thing I have ever done.

*

No, he saw no evil in him, spoke no evil of he who had never laughed nor flirted with her (his slut) because he didn’t need to, because it wasn’t required, for she asked for no effort from him, no narrative, no promises, nothing other than to not be forced to acknowledge what she was. She knew, of course; of course, she knew what she was and what he was too, and how much of nothing they had, how little of lasting worth, but she needed to be able to convince herself in her quiet moments that they understood each other, that they were both the same and that they met each other’s needs, at least. So when he turned her out, literally turned her out of the hotel room 3am one morning as though she was his whore, not merely his slut, when she realised that he hadn’t sought in her what he found wanting in the other, that the other did her duty, that she satisfied just as well as she, she vowed vengeance and immediately put her plan into practice with the reckless enthusiasm that only a woman who has been given the means, the opportunity, to make another woman unhappy is capable of.

*

Memories superimposed upon memories. To tell the truth one must not worry about what is true.

*

I have felt a compulsion to write for as long as I can remember. When I was eight years old I started my first novel. I would add a chapter a day, with some help from Paul Williams, a classmate. I call it a compulsion because I don’t appear to be able to stop, regardless of where I am or what I have to hand. I have drawers full of scraps of paper, bus tickets, and post-it notes on which I have scribbled lines or ideas; my mobile phone has more notes stored on it than numbers; the space on my computer is almost entirely taken up with large word documents. I don’t want to delete or throw away these fragments of prose because they are, albeit indirectly, the story of my life.

*

Once, laid on my side, I longed intensely to be outside, in the jaws of a spider.

*

Isn’t it possible, likely even, that I am viewing the world through the prism of my own insanity, and that this is the reason why everything I experience seems so peculiar, offbeat, and frightening?

*

No, my youngest son saw no malice in the slut, or at least apportioned no blame to her, for these things had to be, had to happen, so that the brother could come back and regroup his mental forces, and so that he (my youngest son) could be his audience, his collaborator, his confidant, his champion, and his messenger too, so that he could pass on to the mother the tall tale of a man who had looked deep inside himself and been stricken, panicked by the ghostly presence of his parent and the north, a mother and a city, let’s not forget, that had at no point pleaded nor prayed for his return. I would never have prayed nor hoped for his return, not even in my weakest moments, because I knew that if he did there would be no good in it. I thought: let him ruin, and spread his bad luck, his hurt, elsewhere, and, if I must record them at all, let me record the tremors from here, with him there, anywhere, away.

*

To live is to meet the misery of the world head-on, not to write about it, nor read about it.

*

Whenever I am on a train I will spend some time looking out of the window, and I am always struck by a painful feeling, an understanding that I will never again see what I am seeing, that even if I take the same train, at the same time, travelling the same route, the sights will not be exactly the same. No single second of your life can ever be repeated; to all intents and purposes, you die thousands of times a day.

*

Maturation is, of course, an ongoing process; a process that, you might argue, ends only with your death. It is, therefore, difficult, perhaps even absurd, to attempt to pinpoint a moment in your life when you became aware of yourself as a adult. Yet, when I cast into the pool of my memories, I am able to dredge up a number of incidents or experiences, which at the time struck me as pivotal in my development towards becoming a man. My first ejaculation, for example. My seed has adorned the faces, the bellies, the breasts, the backs, and backsides, of various women; it has been swallowed and spat out; it has dried slowly into bedsheets and t-shirts; but none were as significant, as world-shaping – for you are the world – as the afternoon it made its debut, dribbling down my own hand.

*

It’s easy to reminisce, because the pleasant or funny incidents push back the darkness lurking at the periphery of each memory.

*

I did not read children’s books as a child and do not remember ever having them read to me. We did not, in fact, have any in the house, and I knew instinctively that, being poor, I should never ask for anything. The only books we owned were a large leather bound collection my father had bought when he and my mother married. These included poetry anthologies, the complete Shakespeare, and so on. Occasionally, I opened them. They smelled of damp and appeared to be written in a foreign language. At the age of around six or seven I did attempt to steal an adventure book from my primary school teacher, but I was caught and ordered to give it back. I was told that if I wanted to borrow something I should say so. I stared into his beard and remained silent. It was impossible; he didn’t understand.

I have never wanted to recapture my childhood and do not consider myself to have an inner child. Whatever is inside me is not playful and innocent and I don’t feel as though it ever was.

*

I cannot continue to present you with flowers that smell like dirty feet.

*

What a world. Like a festering, rotting pighead in space. And we are the fat, and ever-fatter, maggots that feed upon it. Sometimes, quite often in fact, I see people smile, and I have to wonder: are they mad? Or am I mad? Don’t they see? Maybe that’s the way: close your eyes and smile. The world is a horror show. Nothing surprises me. It is always as I expected. When some inequity is uncovered, some baseness, some cruelty…am I shocked? I am profoundly not shocked. It is simply the case that we are looking, yes, we are looking, and inevitably we are finding brutality, misery, and a host of other horrible things. The whole world, I tell you, is like this. Peer into any corner, shine a light on it, and you will see the filth. Take off your gloves and draw your finger along the surface and tell me how it feels. Greasy and unpleasant, isn’t it?

*

I’m frightened of spiders but I can no longer kill them. When I was younger I convinced myself that the way to deal with my fear was to hate, not to love, but now I can’t bear the brown smear, the twitching leg stuck to the wall.

*

I had first met her in Moscow, a meeting that ended in a car crash. I saw her again in Barcelona, where she was on holiday. She had arrived with no money at all. She had money the third time, when I had invited her to England, but she seemed not to value it. She’d smile and laugh, as though the dangers and miseries of the world were not applicable to her. I called her a child. These words came easily to me. But what I didn’t say was how inelegant she made me feel, how dour and unimaginative. I began to wonder if she really existed. Perhaps I died in that car crash and none of this is real, I thought. I awoke every morning amazed to find her next to me.

With her, the world became clear and intelligible. The flowers, the water, the hills. I didn’t like them any more than before, but I saw them and understood them at last. You think that I am simple, because I always smiling, she had said, still smiling; but that wasn’t the case. She was doing the hardest thing of all: making the most of life; approaching it with a kind of manic positivity that made my heart ache with admiration and incredulity. I didn’t tell her any of these things.

*

Perhaps life fades away in stages, like a stain.

*

I started to draw my response. I completed only four panels. A man walks up to me. I’m sitting reading. He asks me what I’m reading. I tell him. He then asks me what it’s about. The fourth and final panel shows my sad, frustrated face.

I dream in words, rather than images. It has only recently occurred to me that this is strange. I see nothing, darkness, blackness, void, but I hear words. Or I sense them.

In the fifth panel, the man waits, a look of concern or perhaps impatience on his face. I am not adept at drawing facial expressions.

The man, I have forgotten to mention, has an overly large head. It is as though his head isn’t really his head, but a false head, a joke head that he has placed over his own, ordinary-sized, head. This is most likely due to my artistic limitations. There are hints at a wider, overriding significance to the individual events. The tease of being able to pull it all together and arrive at an explanation, a satisfactory resolution.

There are clues, which may not be clues, if you understand what I mean by that. In panel number twelve the man is crying. I do not know what I have done to upset him. Perhaps it wasn’t me, however; perhaps the man is having some trouble at home; perhaps this is why he, without any encouragement, has approached a stranger and engaged him in conversation. The man is angry because he feels as though I am making fun of him with my explanation.

I slowly count and recount the panels. The plot isn’t really a plot, although it gives the impression of being one. My dreams are not my waking life. My waking life is a nightmare. The man cries, terribly; his face is contorted. It is with great conviction that I state that I am not sure at all about what I am saying. I draw the tears, which, as I am using a black biro pen, look like large ants, or bullets.

It is possible that I am mistaken and the man is neither crying nor angry, but is, in fact, laughing.

In panel thirteen or fourteen I assure the man that our lives are random and unpredictable, in both large and small scale ways.

In one of the panels, perhaps the last panel, the truly last, I am glumly smoking a cigarette. I hold up one finger, the first finger on my left hand, and then plunge it into the hole made by my right hand. The man laughs, or cries, or whatever. His big head shakes like a dandelion in the wind.

I’m embarrassed by my inability to capture, on paper, a true likeness of a dick and a vagina. My head pounds. The vagina, I must admit, is causing me greater problems than the dick. The man wakes. It is possible that I nudged him. Hey, I might have said, don’t sleep. This is panel something or other. A black bordered panel; a black square with nothing inside.

The man solemnly walks away. I sketch his receding figure. His big head trembles, like a golfball rattling the rim of the hole.

*

Words, like schoolchildren…snot-nosed and uncouth.

*

I don’t watch or read the news. Not anymore. I don’t want to know about current affairs. I’m leaving you to it, for my disdain for humanity was once at such a prodigious level that I was concerned about my mental and emotional well-being. The world is a foul place. It reeks of death and decay. It stings my eyes and nose like cat piss; it clogs my throat like black smoke. It is only in cutting myself off that my anguish and bitterness has eased somewhat. I wake up in the morning now, open the curtains, and look out upon nothing. Nothing, but the gentle twittering of birds and the calm flow of the river I live beside. It is a dull scene, but it is only in this way that I can stomach my existence, our existence; it is only without you, away from you, that I can tolerate my own wretchedness.

*

In Tokyo, I collapsed, and ever since I have been experiencing a ‘dropping’ sensation in my head. Momentarily, I feel as though I am falling, and, as in a real fall, I anticipate the end point as a sudden, devastating impact.

*