They often come to me from different towns or cities. I meet them at the train station, and on each occasion, as we exit, and start the climb towards one of the bars in the city centre, I turn my head and draw their attention to the Park Hill housing estate. I know I shouldn’t do it, but I do. The woman is not the same but this scene is; repeated I don’t know how many times now. Look, I say, and they look. And then I begin my explanation, which, by this stage, is almost scripted; and I’m boring them, I know; and I’m boring myself; but I can’t help it, as I am intensely moved. I didn’t grow up in Park Hill, but it was a place just like it; hard, raw and grey. The design of the buildings mirroring my experience. It’s pretty ugly, they say, or something of that sort. I don’t tell them that I feel ugly too, for this sort of thing formed me. I too am hard, grey concrete. For a while they stopped buses going up there, to the estate where I lived, because children would throw bricks at them. Where did they get such a supply of bricks? Were they stolen from the tower blocks themselves? In my mind I see little gutter kids sitting in the dirt, carefully removing bricks from the base of tall buildings. And in the next moment I see them toppling, in a perfectly choreographed, Twin Towers-like collapse.

On the surface, Domu, by Akira creator Katsuhiro Otomo, is a horror/murder mystery. At a large housing complex, the residents are dying – twenty-five in less than three years – in unusual circumstances. What appear to be suicides, murders and accidental deaths, are, the police think, somehow linked. The latest apparent suicide had, they note, no history of mental health problems and left no note. He also had no access to the key to the door leading to the roof, from which he flung himself, and the door itself showed no sign of being tampered with. At one stage, one of the detectives says that it is a ‘locked roof mystery,’ in a nod to the once popular locked room subgenre, of which Gaston Leroux’s The Mystery of the Yellow Room is a prime example. In the early parts of the manga, Otomo builds his puzzle carefully and expertly, leaving numerous clues and providing a number of possible theories. It could be that there is a serial killer in the housing complex who has a grudge against the residents. Or is that someone has a grievance with the complex itself, someone who was forced out when it was built perhaps? Or could it even be one of the children? Or a ghost or spirit of some kind?

After a while, however, although the ‘mystery’ remains important to the police, the truth is revealed to the reader and the story then becomes more about the housing complex itself. In fact, even from the beginning it dominates the book in a visual sense. It is a huge, brutalist structure, of the kind I grew up in. It is described as ‘really creepy’ by one character; while another says of it that it ‘goes on forever.’ It appears in almost every frame, often in the background, looming ominously behind the residents or the police. Having lived in something just like this, I understand how they function in the mind. It is a little world in itself, a world made up of often vulnerable people, a little world from which it feels impossible to escape. Wherever you are you can see it or you can feel its presence. One interesting thing that Otomo does as an artist is draw important scenes where the lens has panned out, so to speak, to show only the complex, and the speech therefore appears to be coming from the building itself, rather than the characters. It gives the impression of, not only its immensity, but of a community swallowed up by the complex. In this way, Otomo uses it a little like the Bates motel or the house in The Exorcist; it is not directly responsible for the crimes, but is, nevertheless, a symbol of evil.

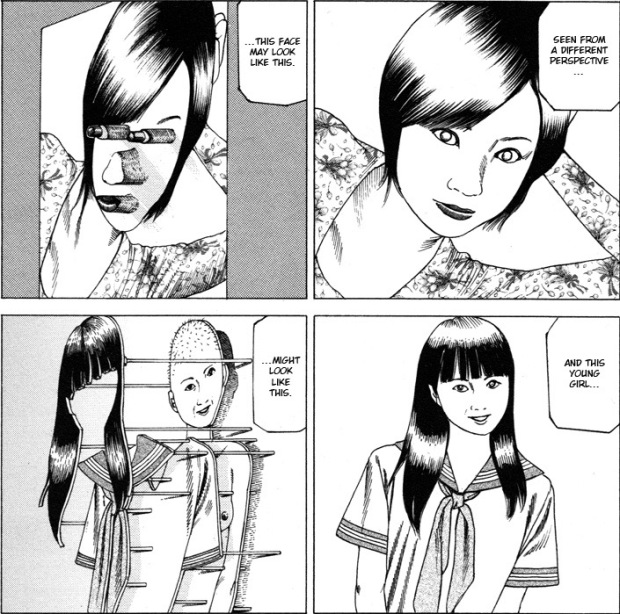

The truth of who is murdering the residents, and the police, is Cho, a senile old man with extraordinary powers. He can levitate, for example, and can move objects with his mind; but, most importantly, in terms of his crimes, he can influence people to do things, such as kill themselves and others. His nemesis is Eksuko, a little girl with similar, if not stronger, powers. The two engage in battle and this provides Domu with its thrilling climax, which is, as far as I am concerned, the best action sequence in manga. On this, my issue with Akira is that there is simply too much of that sort of thing, but here Otomo provides a perfect balance between action and character development and psychology. In any case, it is said that Cho was abandoned by his family, who simply moved out and left him. The murders are, therefore, part play, by a bored old geezer, and part revenge. When he makes someone kill themselves he needles them about their failures, about how awful their lives are. Like the housing complex, Cho could be said to have a symbolic function. He is the suffering, the hopelessness and the destructiveness of the residents. He is the bad spirit, energy or atmosphere.