I have spent my life feeling sane. The sanest, the most rational, the most logical. It was you, I thought with absolute conviction. All of you. You are mad, not me. I was convinced. I laughed at the opinion of others; I scoffed at the judgement of my peers and associates. I denied you; you, who thought me peculiar, eccentric, and unnerving. Until recently, that is. Until I met someone who agrees with me, who believes in my sanity. I met her and suddenly, almost instantly, I lost my nerve. I no longer believe in myself, because of her. I no longer trust myself, because of her. How can I, how can someone like me, be entrusted with something precious? I’ll hurt her, I’ll break her, I’ll ruin her, precisely because of her faith in me, in my soundness of mind and character. I cannot be trusted….because I’m not sane. I see it now, what you see and have always seen. I’m crazy; and a beautiful vase is not safe on a rickety table.

“When you find yourself locked onto an unpleasant train of thought, heading for the places in your past where the screaming is unbearable, remember there’s always madness. Madness is the emergency exit.”

It is perhaps this uncertainty, this feeling of vulnerability, that has brought me back here. I am, it strikes me now, using this as a kind of preserver, a log large enough to hold onto and be kept afloat. By ‘this’ I mean, of course, writing; and reading. The Killing Joke. It took me little over an hour, but it soothed me; it soothes me still. It is not her, it is not us, at least. I have no responsibilities here. I had been given the impression, from the bits and pieces that I had read about it beforehand, that the focus of the story is the relationship between The Joker and Batman, specifically how alike they are, how they are essentially the same. But that isn’t the case. Batman is largely absent, both literally – in that he has little page-time – and in terms of his personality. He is almost a blackhole of a character. A nothing. The one insight we are given into who he is as a man is when he states that he doesn’t want to kill The Joker, that he is afraid that he will kill him or be killed by him. Ultimately, I got the feeling that Moore just wasn’t particularly interested in him, and so neither is the reader.

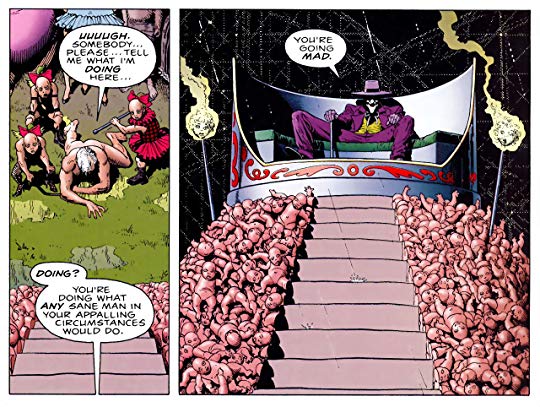

The same cannot be said of The Joker. Moore puts a lot into him. On one level, he is an epic cunt. Just the sort of cunt a reader, or this reader, wants in a bad guy. At one point, for example, he shoots a young woman, paralysing her. No word, no warning. She opens the door and he grins at her and fires. He then strips her and takes photographs. Moore wasn’t messing. The Joker’s not messing. He is undoubtedly a horrible cunt. Yet, Moore also gives us his backstory, where it is explained who he was and how he became what he is. The Joker was a bad comedian, a failing man and husband. His jokes are terrible. I wondered initially if The Joker’s puns were meant to be funny, but Moore’s exposition convinced me that they are deliberately not funny. The man behind the face paint. He isn’t the joker, he is a joke. He’s a bungling burglar too. He agrees to commit a crime in order to give his woman and child a better life. He fails at that also. A loser. The Loser.

It’s clear that Moore wants us to understand The Joker, to empathise with him. He demystifies him, humanises him. It could have backfired. The Joker isn’t all bad, in the way that a supervillain, in my limited understanding of the superhero genre, is meant to be. He isn’t something other, he is simply a man. An average man, a hurting man, a failure, like most of us, who goes mad through misfortune and bad choices. It’s not Batman who we are meant to see in him, but ourselves. Indeed, one of the themes of the story is that he could be you, in the right – or wrong – circumstances. This is what The Joker aims to prove in kidnapping and torturing Commissioner Gordan. A good man, a normal man, a sane man, will go crazy, will break, if you subject him to certain, appalling situations. It’s inevitable, natural, comforting even.

As with everything I have read by Alan Moore, there is a satisfying depth to his ideas in The Killing Joke. Intelligence; no easy answers or conclusions. The Joker is discomforting, not because I saw myself in him, as some may do, but because he is acting out of pain. He is capable of anything, because this awful anything, this madness, distracts him from the pain. It is also worth mentioning that he is drawn beautifully. He is odd looking, without being monstrous or camp. Moreover, some of the other illustrations are impressively creepy, resembling an Aphex Twin video you may once have seen on MTV at midnight. In any case, my favourite part of the story is at the end, and features neither The Joker, nor Batman, nor any kind of traditional comic book hero or villain. A man speaks. Facing forward. Talking to you, it seems. He wants to do something bad. Kidnap a child, perhaps. A little girl. He wants to kidnap her and make her ordeal as terrible as possible. He would rape her, no doubt. The man has a woman and a child of his own. He is not bad, he states, he simply wants to try it, to compare it to goodness. It is this man, without green hair, without face paint, without a bat suit, who is the most familiar to us, and the most frightening.