I never thought that I would become tired of sex. In the last twelve months, however, I’ve done it more times, and with more women, than I had in all the previous years of my life combined; and recently I’ve noticed a change, a hint of boredom creeping into my lovemaking, like the shadow of a pot-bellied man crawling up a bedroom wall. I had once been so easy to please, so straightforward in my tastes, but now? If someone were to suggest the missionary position I would be horrified. The shadow of the pot-bellied man looms larger, and between his legs dangles a most flaccid and unimpressive cock. I have a preference for certain acts, of course, but I’ve never really had any kinks or fantasies. I’ve always found that sort of thing ridiculous, for it suggests to me a mind gone awry, a defect, a glitch in the system. Sex but not sex. Sex incognito. Yet last week I was talking to an underwear and fetish model. She was fresh off a job in which only her feet were of interest. ‘It’s because they’re forbidden, because they’re not the norm, because they’re kind of ugly and dirty; you’re not meant to sexualise them and so they become sexy,’ she said, and while I still didn’t feel any stirrings myself, for the first time I, in my jaded state, understood.

“Beauty belongs to the sphere of the simple, the ordinary, whilst ugliness is something extraordinary, and there is no question but that every ardent imagination prefers in lubricity, the extraordinary to the commonplace.”

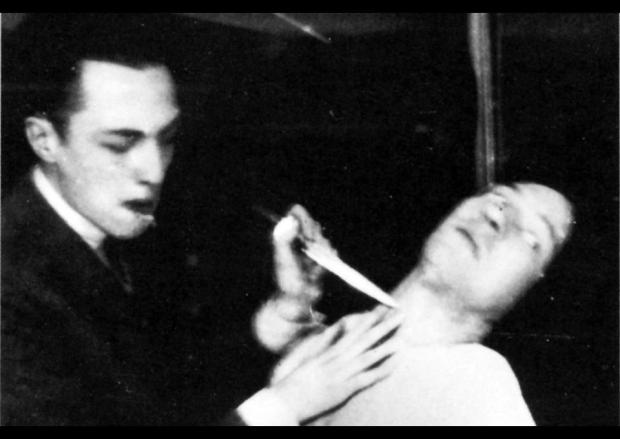

The Marquis de Sade’s 120 Days of Sodom appears to be one of those works that many people have heard of but know little about in terms of the specifics of the story. I was one of the many. In fact, I was under the impression that there was no narrative at all, that it was simply a catalogue of sexual deviancy. And it is that, but there is a frame around the kinks and perversions, in which four libertines gather together – some by way of abduction – a group of men and women, but mostly boys and girls, in a remote castle. There, they have a number of aged prostitutes recount their experiences, which are progressively more extreme, and which they then re-enact with the other inhabitants. This is, indeed, one of the most fascinating aspects of the novel, because it makes an audience of the libertines, almost in the same way that you, the reader, are; and just as the power of suggestion works upon them, there is the chance it will work upon you too. Certainly, not everything contained within will appeal to everyone, or I would sincerely hope not, but there is such a range, and it is so imaginative, that I’d be surprised if there wasn’t something. I think there is a misconception about pornography that people only go to it with, and looking for, pre-established ideas about what turns them on. There is some of that, no doubt, but I also think that, for better or worse, it also suggests, it teaches, it moulds.

While 120 days of Sodom is not a character study, the four libertines are sketched in some detail, to the extent that one is informed of both the length and circumference of their dicks. The Duc de Blangis is fifty years old, and ‘may be regarded as the repository of all vices and all crimes.’ His brother is a Bishop, who is, we’re told, ‘treacherous and cunning,’ and a ‘loyal devotee of active and passive sodomy.’ The President de Curval is ‘the walking image of debauchery and libertinage,’ who has a ‘dreadful squalor about his person that he finds sensual.’ This gentleman’s erections ‘are rare and only achieved with difficulty.’ Finally, Durcet, a financier. He has a ‘woman’s build and all of her tastes.’ In considering the four men a number of interesting ideas and similarities emerge, many of which are expanded upon, or given more weight, as the book progresses. First of all, one may have noticed that each of the men are rich or of noble birth. While de Sade doesn’t explicitly discuss the issue of class, it cannot be a coincidence that every anecdote involves people in a position of power and prosperity. One might say that these are the only people who can afford to use prostitutes, but I believe there is more to it than that.

Throughout, the small number of peasants are the only characters shown in a positive, or sympathetic, light. They are pious, good-hearted, downtrodden, or happy-go-lucky, while the rich have peculiar tastes or are simply monstrous. For example, one poor old woman is dragged from her sickbed and abused by a wealthy man; her daughter, who her mother very much loves and who cares for her, is abducted by the man and likely murdered as part of a sexual act. In another anecdote a working man shits, not for his own gratification, but for a rich man who has paid for this service. So what, if anything, is de Sade saying, indirectly at least, about class? The rich are the only people who have the time and the means and the imagination for these kinds of perversions, that in fact the free time and great wealth enables their imaginations. Secondly, if one can buy whatever one wants, if one can (by virtue of one’s power and wealth) have whomever one wants, then one is likely to become jaded very quickly. Therefore, to be a libertine, to be aroused by, to engage in, extreme or unusual sexual acts is, in this instance, an end point, it is arrived at as a way of reinvigorating dulled senses.

I have already used the term libertine multiple times, and that is because it is insisted upon in the text. Barely a page goes by in which it doesn’t appear more than once. To be a libertine is to indulge oneself, sensually, to excess, without regard to conventional moral principles. This is both the way of life and the philosophy of the four central characters; it is this that bonds them together. Far from having one particular kink, the men are interested in anything that is unconventional, anything that conventional society would deem wrong or disgusting, including rape, torture, incest, and murder. Indeed, anything criminal adds to their enjoyment, by virtue of how shocking, how frowned upon it would be. Perhaps this anti-conventional attitude is the reason why women are so scorned by the four libertines (and by the majority of the men in the book). Make no mistake, they are vehement misogynists, to an almost laughable degree. For example, there are numerous instances where a woman showing her vagina or breasts to a man sends him into a rage. It is, in almost every story, the arse they want! Always the arse! There are, indeed, several rhapsodic speeches on the subject, such as when one of the libertines salutes ‘divine arses! How I reproach myself for the tributes I stole from you! I promise you an expiatory sacrifice – I swear on your alters never to stray again for the rest of my life!’ The arse is of course not uniquely feminine.

“Only the law stands in my way, but I defy it – my gold and my influence place me beyond the reach of those crude scales meant only for the common people.”

As I sat down to write about 120 Days of Sodom there were a large number of themes that I intended to explore. My notes, in fact, totalled over a thousand words, and much of that I still haven’t touched upon, and will not, including the topics of nature and religion. I realise now that it is inadvisable, if not impossible, to discuss everything of note in detail. This review will have to serve as a kind of introduction, if it has any use at all. Bearing in mind the name of the author, one thing that it seems necessary to include is the role of sadism within the book. Surprisingly, sexual torture, and the pleasure gained from it, makes up only a small part of the prostitutes’ stories. However, the main reason for this is because the book is unfinished, and only one whore – she who is tasked with outlining the simpler pleasures – is able to give a fully fleshed account of her experiences. One is left in no doubt – and de Sade’s own notes attest to this – that there were greater horrors to come. Yet there is still, even within the ‘finished’ part of the manuscript, much that is disturbing, certainly when removed from the atmosphere of the text as a whole. For example, the inhabitants of the castle, aside from the four libertines of course, are not allowed to shit unless given permission and are not allowed to wipe or clean themselves. This is because the men have designs upon the shit, but also because they enjoy the power, they enjoy how unhappy it makes the boys and girls.

Throughout the book, de Sade makes it clear that almost none of the young people, nor the men’s wives, are willing participants. They shit in the captives’ mouths, and have them shit in theirs. They fondle, maul, and force them to suck and swallow, they rape and fuck arses and cunts. The disgust and pain their victims feel during these abuses is commented upon, albeit only in passing. It is this, more than the acts themselves, that turns the old lechers on. Within the castle there is a system of punishment, which the reader never has full access to, but which we are informed will be barbaric, potentially fatal. The victims, who are innocent both in terms of their overall situation and often in terms of the ‘crime’ they are charged with, are constantly reminded of the compassionless nature of their judges. The situation within the castle is, therefore, absolutely not the form of sadism that is currently en vogue, it is not a consensual exploration of mutual fantasies involving a master and a slave, a dom and a sub, although there is some of that within the stories the first prostitute tells. In any case, there were occasions when, rather than providing a libertine manual, I felt as though it was de Sade’s aim to torture his reader, to make them his victim; and yet, if so, he failed.

“If it is the dirty element that gives pleasure to the act of lust, then the dirtier it is, the more pleasurable it is bound to be.”

Before I finish, I want to return to a word I used earlier, which may have struck you as strange, or even disconcerting, given the context, which was ‘laughable.’ There is, without question, nothing funny about kidnapping, misogyny and sexual abuse. When I was reading A Sentimental Novel by Alain Robbe-Grillet last year I was deeply troubled by its contents and had to quit before the end. 120 days of Sodom is, however, or was for me, extremely amusing in places, because it is ridiculous. There is a marked difference of tone between this book and Robbe-Grillet’s. First of all, one never believes in the characters or the situation. I could not buy into de Sade’s reality. The four libertines are cartoonish, vaudeville, over-the-top; they stop just short of twirling their moustaches and laughing in an exaggeratedly sinister fashion. Moreover, consider again some of what de Sade tells you about them: one of them can’t get an erection, one of them only fucks arses and has his own fucked, and two of them have prodigiously large dicks. It’s terribly hard to take any of them seriously.

These men all have an insatiable sexual appetite, to the extent that they appear to be turned on, to be able to fool around, all day, every day; and most of them come multiple times. They are truly Herculean! Consider, also, some of the acts, the shitting in particular. It is no exaggeration to say that the libertines devour three or four turds a day each, and none of them end up unwell. They even put their captives on a special diet in order to have them produce especially tasty shit. I don’t want to labour over the scat too much, but it dominates the book, and there came a point when, despite having no interest in shit myself, be it sexual or otherwise, I started to gleefully anticipate the ceremony. de Sade had put me into a state of near delirium or hysteria. Every anecdote would end, I knew, with one person shitting in another’s mouth. It was like being locked in a room where someone tells you the same joke over and over again until you’re on the point of insanity and joyously shouting out the punchline in unison with your captor.

In other areas, the repetition was more of a issue. I am aware that de Sade wrote the book in prison, and that it is, at noted previously, unfinished. It is likely, therefore, that even the ‘completed’ part of the text is only a draft of sorts, and so it feels churlish to criticise, but there are frequent passages that are interminable. For example, I do not know how many times one needs to be told that the Duc thigh-fucked Zelmire, but it is certainly less than forty. Nor does one really need to be told, over and over again, who took who into the cupboard, especially as you are never informed as to what happens in there. There are, moreover, other instances of this sort, whereby de Sade will keep things, certain acts or events, from the reader, because, he states, they are too extreme for this particular part of his narrative and would be out of place. Which begs the obvious question: why tell us at all then? In any case, my enjoyment was not spoiled by these flaws. I did not think, even for long periods during which I read it, that I would be able to say that I love 120 days of Sodom; and yet I do. Perhaps I am even more jaded than I thought. The shadow of the pot-bellied man looms ever larger.