In 874 CE a Norwegian chieftain, Ingólfr Arnarson, became the first permanent settler on the island that came to be known as Iceland. Ah, truly an independent man! One can’t help but think that Gudbjartur of Summerhouses, the dominant character in Halldor Laxness’ Independent People, would have approved of such a state of affairs. As the novel begins, Bjartur has purchased his own piece of land, after working, for eighteen years, for the Bailiff. This is, despite the measly nature of the land and the shabby dwelling upon it, a momentous occasion for him; he is, at last, a free and independent person. Indeed, Bjartur prizes this independence above all else, so that it becomes almost a mania with him. For example, in the opening chapter there is told the story of the witch Gunnvor, out of which has grown a kind of superstition that one must, when passing her so-called resting place, ‘give her a stone.’ Bjartur, however, refuses, even when his new wife begs him out of a fear of bad luck. He would, it is clear, rather make her unhappy than compromise his principles, than for one moment sacrifice the smallest amount of his freedom [i.e. his freedom to act as he pleases]. Likewise, when she later yearns for some milk, he makes it clear that he will not countenance it because he cannot produce it himself. Bjartur will not ask for anything from anyone else, as he sees this as begging; nor will he accept gifts either.

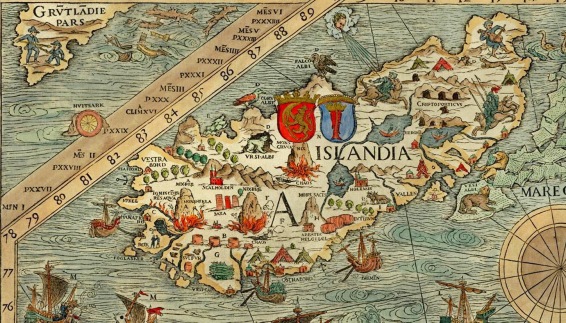

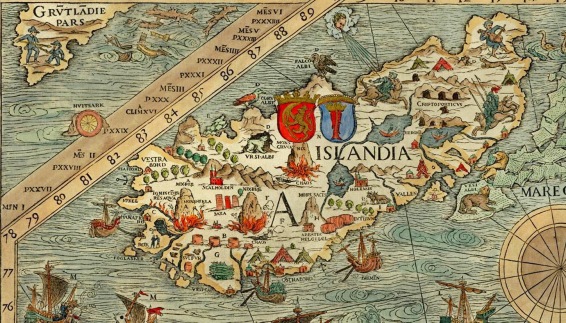

[Iceland on the Carta Marina by Olaus Magnus]

One might wonder then how one is to approach Bjartur, what one is to make of him, for there are elements of his personality and behaviour that are agreeable and elements that are, in contrast, entirely disagreeable. First of all, we instinctively root for those who strive for freedom; as we do those who live in accordance with their principles, and those who are prepared to work hard. However, his behaviour has disastrous results for his family. Hard work, principles, ideals, freedom, all that is well and good, but if the result is overwhelming misery then one must question whether it is worth it, whether the man who brings down this misery upon his family [if one wants to say that he does – and you do not want to blame economic conditions] is not actually a good person. This, for me, is one of the key questions that the novel raises: just how important are principles? Are they worth sacrificing your health and happiness for? I must admit that I was never really sure how I felt about Gudbjartur of Summerhouses. He has many admirable qualities, and he is capable of tenderness, but he is equally capable of monstrous behaviour.

“It was pretty miserable wretches that minded at all whether they were wet or dry. He could not understand why such people had been born. “It’s nothing but damned eccentricity to want to be dry” he would say. “I’ve been wet more than half my life and never been a whit the worse for it.””

It is interesting in light of all this to consider that Laxness was, by all accounts, a Maxist. Indeed, he is said to have visited Russia prior to commencing work on Independent People and was very impressed. Even without this knowledge it is clear that with the novel Laxness was, to some extent, making a political statement. Throughout characters engage in political discussions, pass comment on the governing of the country, and wax philosophical about the status of the working man. Moreover, it is significant that the title is plural; Laxness is clearly not, therefore, only concerned with one resolute man, but, rather, an entire country or class. It is worth noting, in this regard, that from 1262 to 1918, Iceland was ruled by Norway and then Denmark, and that the country itself only became independent in 1918, shortly before the novel was written.

Yet if you accept that Laxness was concerned with an entire class or country, and one considers the Maxist sympathies, then his message seems somewhat obscure [although this may have much to do with my own ignorance]. Marx was himself concerned with labour, production, and the proletariat, all of which obviously play such a big part in the narrative of Independent People. For the German, giving up the ownership of one’s labour is to be alienated from one’s own nature, resulting in a kind of spiritual loss. This seems somewhat in line with how Bjartur is presented, a man who certainly does own his own labour. However, Marx also advocated that the proletariat should have class consciousness, that they ought to organise, and ultimately challenge the prevailing system, which is not at all in keeping with Bjartur’s behaviour and opinions, as he is suspicious of political engagement and, well, men-at-large. For example, when the Bailiff’s son, Ingolfur, broaches the idea of a Co-operative Society for farmers, which would, he claims, prevent exploitation, Bjartur isn’t at all interested.

If Bjartur was intended as some kind of anti-capitalist hero then the book fails, because he is not necessarily against capitalism [he defends the merchant], he is simply against anything, or anyone, he deems to be in some way attempting to deny him freedom or independence. For Bjartur, one can be as ruthless and money-grubbing as one likes as long as you don’t interfere with him. Moreover, this free man, this man who owns his own labour, only ends up exacerbating the suffering of innocent people. As the novel progresses, the reader may legitimately ask if he, or certainly his family, wouldn’t have been better off remaining in the pay of a wealthier employer, if that wouldn’t be a more comfortable and therefore rational way of living. In fact, while one might look to the Bailiff and his wife – who periodically appears in the text in order to make glib and patronising statements about the working class, about how only poor people are truly happy, and how much she envies them. She contrasts this, of course, with the hard life of being a bourgeois employer, where all your money goes on paying wages and one cannot [the horror!] afford that dress you’ve had your eye on for a while – as the capitalist villains of the piece, the more I thought about it the more I realised that Bjartur himself could be called a capitalist, just not in the way that we tend to understand that term these days.

When someone says capitalist we [or certainly I] tend to imagine someone rich, with at least one thriving business, which is run on the toil of hired workers. Well, Bjartur is categorically not rich; nor does he own a thriving business; and the only workers he has are his own family. Yet his situation is a capitalist model; his farm, although not at all flourishing, is a private enterprise and his family are absolutely exploited as a means of production. The kids, the wife, all are expected to put in extremely long hours, and far from being rewarded commensurate to their efforts are actually given very little to eat, live in wretched circumstances [a small, foul-smelling, leaky hut] and have only rags to wear; indeed, these workers are actually sacrificed in order to protect the business’ assets [i.e. the sheep, which are given preferential treatment]. It is likely that I am wrong about all this, as I am admittedly no expert on Marxism and so on, but It was only when this interpretation came to me that the politics of the novel started to make more sense. Marx wrote about the “despotism of capital,” and that phrase could be seen to sum up this book.

I worry that so far I have made Laxness’ work seem horribly dry and grim and unapproachable. I mean, it is grim, there’s no way of getting around that, but it is not without warmth and humour and beauty either. Bjartur, although a kind of tyrant, is also a funny character, particularly in the opening stages of the novel; and even when things are at their blackest there are still moments of absurd comedy, for example, when Bjartur says, “A free man can live on fish. Independence is better than meat.” Furthermore, there is some fine nature writing which acts as a contrast to the unrelenting drudgery. In fact, Laxness’ prose is what makes the novel bearable. While I dislike throwing the word poetic around, because I think it is often used merely as a way of describing so-called superior or flowery writing, it is apt in this case; the Icelander was, I believe, actually a poet; and, well, it shows.

“Shortly afterwards it started raining, very innocently at first, but the sky was packed tight with cloud and gradually the drops grew bigger and heavier, until it was autumn’s dismal rain that was falling—rain that seemed to fill the entire world with its leaden beat, rain suggestive in its dreariness of everlasting waterfalls between the planets, rain that thatched the heavens with drabness and brooded oppressively over the whole countryside, like a disease, strong in the power of its flat, unvarying monotony, its smothering heaviness, its cold, unrelenting cruelty. Smoothly, smoothly it fell, over the whole shire, over the fallen marsh grass, over the troubled lake, the iron-grey gravel flats, the sombre mountain above the croft, smudging out every prospect. And the heavy, hopeless, interminable beat wormed its way into every crevice in the house, lay like a pad of cotton wool over the ears, and embraced everything, both near and far, in its compass, like an unromantic story from life itself that has no rhythm and no crescendo, no climax, but which is nevertheless overwhelming in its scope, terrifying in its significance. And at the bottom of this unfathomed ocean of teeming rain sat the little house and its one neurotic woman.”

Moreover, as with all great novels of some heft, there are certain scenes in Independent People that will likely stay with you long after reading the book. For me, there are two in particular. First of all, there is the chapter when Bjartur leaves his wife Rosa on her own over night with his favourite gimmer [one of the Rev. Gudmundur’s breed, no less!] as company. Rosa, who has been on edge ever since not being allowed to give Gunnvor a stone, sees in the sheep’s frightened bleating some kind of evil omen. Laxness takes this potentially ridiculous set-up and manages to imbue it with a creeping tension and horror, until Rosa finally snaps and executes the gimmer. It is, in my opinion, one of the most powerful descriptions of madness in literature. The other big favourite of mine is when Bjartur goes in search of the sheep, for he doesn’t know it is dead, and spots a group of reindeer. He decides, being a strong-willed independent man, that he is going to capture the buck for meat. This is no easy feat, of course. During the struggle he climbs upon its back and the buck takes him into the river Glacier in an effort to throw him.

When I read another of Laxness’ most well-known works, World Light, last year I felt as though the characters lacked depth; it struck me that they had a signature mood or quirk, and that is all. As I reread Independent People I was starting to get the same feeling about Bjartur; yes, he has mania for independence and freedom…I get all that, I enjoy it, but one reaches a stage where this point has been hammered home so frequently in the first one hundred pages that you start to worry about another four hundred of it. What sets this book apart from World Light, and many other lesser novels, is that Laxness knew when to change it up. So when Bjartur’s one-man-show [he has a wife, of course, but she’s only really there for him to harangue about independence] starts to creak a bit, when it’s becoming repetitive, the author introduces a number of interesting new characters. In a way, one could criticise this move, for it is so abrupt, but providing Bjartur with a new wife, mother-in-law, and children gives the book fresh impetus. Moreover, this family is more finely crafted, have a greater emotional range and a more sophisticated inner life; this is particularly true of the children, Nonni and Asta, who are wonderful creations.

I’ve never been one for child worship, for finding a child’s misfortune worse than any other; I find that attitude quite odd, in fact; but Asta, Bjartur’s daughter from his first marriage, ruined me. She was born in extraordinary circumstances, tragic circumstances, and her life at Summerhouses proceeds in a manner no less tragic. There are numerous books that have moved me, many that have needled my personal sore spots [which this one does too, actually – anything to do with poverty tends to affect me emotionally], but this, as far as I can remember, is the only book ever to make me cry, to provoke a tear into dribbling miserably down my cheek. And it is all Asta’s fault. I’m not even sure why she got to me so much; she’s a sensitive, trusting slip of a girl, who, in her naivety or innocence, wants so little [her joy at being given an old worn dress of her mother’s all but finished me off], but, crucially, unlike her father, she does want; she is inquisitive, eager to learn. Maybe it is that: desiring such meagre or basic things, and being denied them. Or perhaps it is simply that having been brought up by a struggling single mother I just can’t bear to see women unhappy. I don’t know.

It is worth noting, in conclusion, that, after all the exhausting and frequently oppressive bleakness, there is, towards the end, a tiny shaft of light, a few whispered comforting words that suggest that love, at least, will endure. Ah, hold onto those words, store them in your heart, because a little hope, even blind hope, is the most precious thing of all.