Whenever the subject of the Nazi Party is raised talk inevitably turns to the extermination of what they – the Nazis – considered to be the ‘racially impure.’ Less, it seems, is known about, or spoken about, certainly in my experience anyway, the programmes to cultivate an Aryan population, which was, they hoped, to spring up in place of the murdered millions. The Lebensborn, for example, which, amongst other things, encouraged married men to mate with similarly racially pure women, with the children often being adopted by SS officers and their families. In 1936, Heinrich Himmler, failed chicken farmer and occultist, wrote to members of the SS that the purpose of the Lebensborn was to ‘support racially, biologically and hereditarily valuable families.’

When the Nazis began to occupy certain areas of Europe, the plan evolved to include not only breeding but kidnapping also. Indeed, it is estimated that 400,000 Aryan, or Aryan-looking, children were spared the concentration camps and taken from their parents and transferred to Germany for ‘Germanisation.’ Poland bore the brunt of these abductions, to the tune of 200,000 children. Himmler again: ‘we should exclude from deportations racially valuable children and raise them in old Reich in proper educational facilities or in German family care. The children must not be older than eight or ten years, because only till this age we can truly change their national identification, that is “final Germanization.”‘

There are of course many worthwhile novels about the Holocaust, but Michel Tournier’s The Ogre is the only one that I have encountered that focuses on the Nazi obsession with eugenics and the [hoped for] next generation of German children. The book begins, however, in France, with the ‘sinister’ diary entries of Abel Triffauges. As with much in the novel, the word sinister has multiple meanings. Firstly, it refers to Triffauges writing with his left hand [the Latin adjective sinister means ‘left’], as a result of an accident that prevents him using his right. Secondly, it has Heraldic significance, and Heraldry plays a role in the book. Finally, and most importantly, is the common meaning, which is to suggest evil or threat.

While it isn’t immediately clear what kind of threat Abel Triffauges may pose, he certainly gives the impression of being a very strange man. Indeed, the first words are an accusation, from Rachel, a Jewish woman with whom he has been having sex: you are an ogre. And what is an ogre? Triffauges says that it is ‘a fabulous monster emerging out of the mists of time’ and is pleased by this description, for he believes that there is something ‘magical’ about himself. His soul, he continues, ‘lit the earth and made it spin’; and there is, he states, a ‘secret collusion’ connecting what happens to him and what happens in general, a connection between his own personal history and that of the world.

“There’s probably nothing more moving in a man’s life than the accidental discovery of his own perversion.”

During the compelling opening ten pages I had extremely high hopes for the novel, was excited about the prospect of spending another 350 pages with such an erudite, intelligent, meglomaniac. However, as the sinister writings further unfold Triffauges focuses more and more on his childhood, specifically his educational experiences, and some of my enthusiasm waned. Perhaps I have simply read too many European novels about schooling authored by men. They all seem to follow a kind of formula, that includes a whiff of homoeroticism and a large dollop of sadism/masochism [see also: Hugo Claus’ Sorrow of Belgium and Robert Musil’s The Confusions of Young Torless etc]. I am sure Tournier would argue that this long section is necessary, in light of what is to come, but I could not quite grasp the connection, beyond the obvious: that both halves of the The Ogre are concerned with children and childhood. What I mean by this is that it isn’t clear to me how most of Triffauges experiences as a ‘puny and ugly’ child himself relate to his actions in Nazi Germany, or explain his obsession, more that his writing about them is actually an example of this obsession.

In any case, as the sinister writings come to an end The Ogre switches from the first person to a third person narrative, relieving the book of some of the excesses of style so reminiscent of Vladimir Nabokov and Lolita in particular. In this half [more like two-thirds, in fact] of the novel the emphasis is on World War Two, and it is revealed how Triffauges becomes involved with the Nazi Party. In leaving behind some of that Nabokovian excess The Ogre flourishes, serving up some of the most extraordinary war writing I have read. Indeed, there is a section about hunting stags that will stay with me for a long time. Particularly memorable is the scene involving the petulant psychopath, and master of ‘deciphering messages in the dejecta of animals,’ Hermann Goering and his pet lion. Goering is ‘dressed in an elegant pale blue kimono, sat at the table with half a roast boar in front of him, brandishing a leg of it like Hercules’ club,’ while the lion ‘sat beside avidly watching the piece of game being waved back and forth over its head.’ I must admit to laughing so hard I had to put the book down for a moment.

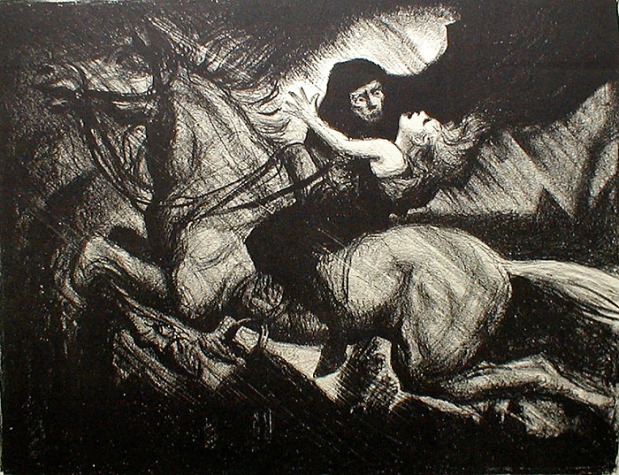

While it is now most commonly referred to as The Ogre, Tournier’s novel has previously been translated as The Erl-King, which is also the name of a famous poem by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. Goethe’s poem is based on a Germanic folktale and features a malevolent figure who preys on children. It is therefore not difficult to spot the connection between this and Tournier’s work when Triffauges, now a trusted aide, begins to recruit for the Nazis amongst the local youths. What is interesting about this aspect of the novel, however, is that the Nazis and the giant Frenchman do not share an ideology. For Triffauges, who calls war ‘an absolute evil’ and who states that a man ‘hagridden by the demon of purity’ – including racial purity – ‘sows ruin and death around him’, the recruitment is a personal vocation. Simply put, children are ‘a little island of reviving freshness’ and so he wants them around him.

“The moth flies on wings of love toward the electric light bulb. And when he gets there, close to it, as near as he can be to that which attracts him irresistibly, he doesn’t know what to do. He doesn’t know what to do with it. For indeed what can a moth do with an electric lightbulb?”

I am not at this stage entirely sure whether the inconsistencies apparent in Trifffauges character are a strength or a weakness for Tournier’s novel. During his sinister writings in particular one is given the impression that the giant is a pedophile, that his interest in children is not innocent. However, it is also the case that he never explicitly harms or abuses any of them; indeed, he likens himself to St Christopher, and appears to see his role as one of carrying children to safety [this is in fact how the book ends]. Perhaps Tournier is trying to make a point about naivety and how much evil can be done in the pursuit of goodness, but I don’t really buy that because he gives too many broad hints as to Triffauges’ dark side, for example, having him identify with a murderer and describing his hands as ‘stranglers claws.’

What is clear, however, is that, in a book obsessed with symbols, he is, or his activity is, a representation of Hitlerism. Hitlerism it is that is the real ogre, the child-stealer. Indeed, there is a scene in the book when the Frenchman comes upon a group of naked young girls, and when he asks what is happening he is told that it is the Fuehrer’s birthday. On this day, Tournier writes, the ogre of Rastenburg demands of his subjects ‘the exhaustive birthday gift of five hundred thousand little girls and five hundred thousand little boys, ten years old, dressed for the sacrifice, or in other words naked, out of whose flesh he kneaded his cannon fodder.’