Excuse me if I begin this review by talking a little bit about myself. Although do not fret, for very soon I will turn my complete attention towards that great man – yes, great – who is no longer with us and yet whose influence is felt now and will be felt with even greater intensity as the years pass. My name is Rudolf Spenglebrauschnitlespritzer. I was born of Catholic parents or, more specifically, of one parent – my father was lapsed to such an extent that one would doubt he was ever anything but – in the industrial heartland of the north of England. I first met [P] during our schooling, despite my being older than he by 18 months. Please, forgive these preliminaries, but I have never written a review before and do not know how to proceed in the best manner, in such a way as to maximise reader enjoyment. I can proceed only as the mood takes me, as the events come to me.

Young [P] was, of course, despite being destined for the greatness that I have already made mention of, not immediately striking as a personality. He was reserved, rather than shy. Without wishing to contradict myself, I would say that this reserved nature was striking, or was – and this is perhaps more accurate – intriguing. One felt that he was not afraid to talk to you, or embarrassed, but that he did not want to. I can’t say, even though I knew him from childhood all the way up to his death, that he and I were ever close. He would, for example, call me Spenglebrauschnitlespritzer, never Rudolf. And yet this man, this standoffish, reserved man, chose to compose, and post, the most personal book reviews. How to account for that, that tension? I do not know. I know that he was good at it, though, that his talent was enormous.

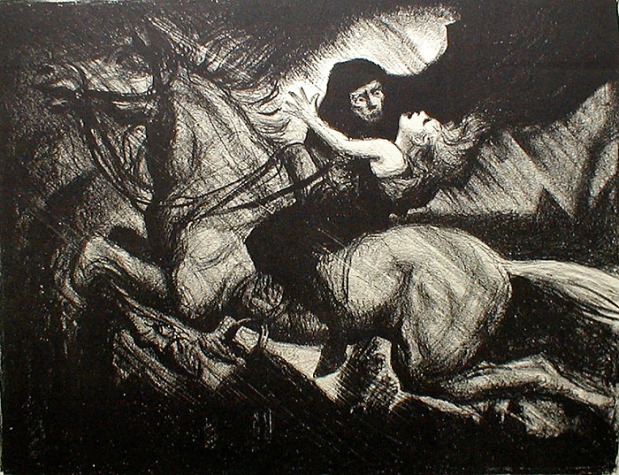

Before his death he was working on a new review, and I can’t help but feel unsettled by it. Simply thinking about that final work, that dark work, the now forever incomplete work that would have elevated him to stratospheric heights of fame, even within his own time, makes my flesh crawl. That work was a review of Doctor Faustus by Thomas Mann. And so we come to the crux of the matter, the reason for my review. When [P] passed away in mysterious circumstances I was surprised to find that he left me not only his incomplete work on Faustus but a manuscript; this manuscript is, to say the least, alarming, and I have thought long and hard about whether I ought to share it with the public. The two men featured in this manuscript are unrecognisable to me. In any case, I present it here, in full and with no amendments. Let it serve as a testament to my friend, and as a warning.

I woke abruptly, perhaps from an unwelcome dream, to find that I was not alone. I had taken to my bed alone, for sure, and I had slept for some time, alone. How now had I company? And not just company, but a partner, for the body that was with me was – I swear it is true – actually beside me. My back to the presence, I felt the breath on my neck, hot breath, like the heat from a candle flame. Slowly I turned around.

He: Hello, [P].

I: Who are you?

He: Why the surprise, why the glum face? Are you not accustomed to waking up to a strange body beside you in bed?

I: Never like this, no. I ask you again: who are you?

He: Oh, I think you know.

I: What is your name, then?

He: They have given me many names; some I like more than others. But, again, names have never been such an issue for you before, so why belabour the point? Call me P.B., if you must, although that one is your own creation. Others know me as Mammon, or Satan. Take your pick, son.

I: Satan?

He: Don’t give me that look. You knew this day would come.

I: I guess I did. What do you want?

He: To help you. Throw me an extra pillow, will you? Thanks. I want to help you, son. Tell me, have you read any good books lately?

I: Are you trying to chat me up?

He: Ha! Believe me, I could have you anytime I wanted. I wouldn’t need to creep into your room late at night. Books, boy?

I: Yes, Doctor Faustus by Thomas Mann.

He: That’s a great book.

I: Yes.

He: Going to write a review of that one, my boy?

I: I should think so.

He: You wrinkle your nose when you lie. I am the king of lies; there’s no way of fooling me. You won’t review Doctor Faustus; you’ve tried already and you found it impossible.

I: That’s right. I don’t know why, but I can’t seem to compose a satisfactory review.

He: You were drunk, quite often, while reading it.

I: It’s not that. It’s so dense, so static, so abstract. There is so little narrative momentum. How do you review something like that?

He: I could tell you.

I: Please do.

He: And for me? What would I get in return?

I: I don’t know. What do you want?

He: Ah, that is why I am here. To make a bargain with you, to strike a deal.

I: You suggest that I have something you want, doesn’t that put me in a position of power?

He: You always were a clever bugger. Talk to me about the book; did it move you, son?

I: Yes. I was very surprised about that. I identified with Adrian very much. Not the genius part, I wouldn’t say that…

He: How modest of you!

I: …but he is an isolated figure, in many ways. Intentionally so; by which I mean that he isolates himself, is not isolated by others. I feel that way a lot of the time, as though there is a barrier between myself and other people, as though I talk to them from behind glass. I must confess that I am to blame for this situation, that I encourage it. Indeed, Adrian is aloof, which is something I’m accused of more often than anything else.

He: The book isn’t about you, boy.

I: I know that. Perhaps it is part of my self-obsession that I look for myself in all things, that I only truly enjoy something when I can link it to my experience of the world.

He: Adrian is mad though, don’t you agree?

I: He certainly descends into madness. Was he always mad? He was always strange, yes, always peculiar in relation to others. I have a condition…

He: I know all about that.

I: …and one of the consequences of this condition is obsessiveness, a kind of intellectual obsessiveness, whereby I can get easily trapped inside my head to the exclusion of everything, and everyone, else. I saw that in Adrian. I couldn’t say whether it was intentional, if Mann meant to present him as someone with that kind of condition or whether he merely saw it as a way of…

He: Describing the process of a creative genius?

I: No. You’re putting words in my mouth. One can be obsessed with creative endeavours without being a genius.

He: It is so. Yet wasn’t Mann, quite plainly, making that link between genius and madness?

I: Yes, I guess so. Adrian deliberately contracts syphilis, a disease linked to madness. He catches it by sleeping with a woman.

He: Bummer.

I: An act of love, perhaps? Is he saying: I’ll take you, I want you, despite the consequences, despite your illness? That would be out of character though, I must admit.

He: Don’t speak to me of love, it gives me migraines.

I: In any case, as the disease takes hold Adrian’s creativity increases. Do you know Nietzsche?

He: I know him very well. We play golf on Tuesdays.

I: Nietzsche is said to have died of syphilis. His later years were characterised by an almost excessive creativity. The French writer Alphonse Daudet is another who had the disease. Quite apart from specific symptoms, there is that cultural link between the illness and creative people. What Mann was trying to say about that, I don’t know. On one level you could argue that Adrian’s genius as a composer wasn’t ‘part of him,’ wasn’t a necessary part, in that he had to become mad in order to deliver it. Or you could argue that the madness was a door which allowed the genius to step through and be exposed.

He: Very good.

I: Then there is the war. The German question. What can you say about that?

He: I don’t know, son. I was rather busy during that time.

I: That the man writing Doctor Faustus, the narrator, is living through the second world war…what was Mann getting at? That art or culture is, in a practical sense, not possible in those circumstances? That clearly isn’t the case. There are many instances of great art being born in times of war. Is he trying to say something similar to what Adorno said about how art is morally impossible after Auschwitz? That to engage in art, to create, after such atrocities is barbaric? One could even say Satanic?

He: Steady on, old chap. You’ll give me a complex.

I: Oh, I just don’t know. This is why I cannot review Doctor Faustus.

He: Hush, child. You’re doing fine. But aren’t you forgetting something important?

I: What?

He: Me, you cretin.

I: Ah, yes. You. What about you? You have the best tunes, they say, and you appear in the best books too. The Faust legend. The encounter with the horned-one. What do I have to say about that?

He: Nothing?

I: Nothing of any note, sir. Adrian speaks to the Devil, makes a pact with him. The usual stuff: his soul for a reward, for the ability to compose something truly special. What is interesting is that Mann allows you to make up your own mind about whether the conversation, the pact, really happened. Adrian is crazy, and the Devil acknowledges that. Is it his madness that allows him to see the Devil? Or is it his madness that causes him to see the Devil?

He: What do you think?

I: What do I fucking know? I’m in bed with Satan right now! Clearly, I’m not qualified to make that call.

He: So what do you say, boy? I’ll give you a review, the best review ever written.

I: Y’know, I’d rather we had done this at a crossroads. Making deals in bed feels…kinda wrong.

He: But what do you say?

I: Ok. Sure. You can have my soul; it’s a pretty lousy thing anyway.

He: Marvellous. Ok, so this is how it works. Write up this conversation and leave it for your friend to post, that Rudolf Spenglebrauschnitlespritzer. The review will go…ayoop…through the roof, they’ll love it. Anything that has me in it is a winner. Of course, you won’t be around to enjoy the adulation. You’ll live for, oh, maybe a few more days. Yeah, you’re pretty much a dead man walking. I forgot to mention that? Small print is a bitch. Always read the small print, boy.

I: A few more days? Can’t you be more specific? I’ll be on tenterhooks.

He: Ok, so you’ll hear a song, I won’t say when but soon, perhaps when you’re in the supermarket, or on a bus or in the toilet. It’ll be ‘our song.’

I: Elton John?

He: What? That’s Your Song, you idiot.

I: Ok, so, what’s the song?

He: Boyz II Men ‘End of the Road.’

I: I love that song! Some people think it is cheesy, but fuck ’em. That spoken word bit at the end? ‘All those times you hurt me, and just ran out with that other fella…’ Fucking brilliant.

He: It’s a cracker. So, yeah, when you hear that song you have exactly 24 hours left. Make the most of them. If you want a tip I’d say hookers are a good place to start. Lots of expensive hookers.

I: Expensive hookers. Ok. Thanks.

The manuscript ends here. I don’t want to speculate about what [P] was going through that night, whether his visitor was real or imaginary. Clearly he was real for him. I can speak, however, about the accuracy of the prophesy, for [P] died of unknown causes within four days of the date at the top of the manuscript in my possession.