I did not read children’s books as a child and do not remember ever having them read to me. We did not, in fact, have any in the house, and I knew instinctively that, being poor, I should never ask for anything. The only books we owned were a large leather bound collection my dad had bought when he and my mother married. These included poetry anthologies, the complete Shakespeare, and so on. Occasionally, I opened them. They smelled of damp and appeared to be written in a foreign language. At the age of around six or seven I did attempt to steal an adventure book from my primary school teacher, but I was caught and ordered to give it back. I was told that if I wanted to borrow something I should say so. I stared into his beard and remained silent. It was impossible; he didn’t understand.

I have never wanted to recapture my childhood and do not consider myself to have an inner child. Whatever is inside me is not playful and innocent and I don’t feel as though it ever was. In this way, perhaps The Lonely Doll would have been then, and is now, the perfect children’s book for me, the perfect evocation of what childhood meant, and means, to me. It is the story of a lonely doll, of course, who ‘had everything she needed except somebody to play with.’ The girl, who is called Edith, prays every day for some friends and eventually gets her wish when two bears appear at her door and move in with her. However, if that sounds cute or magical, the reality, the presentation, of the story is anything but. It is, in fact, deeply odd and at times genuinely unnerving.

The first thing you notice is the photographs. There is some narration, but most of The Lonely Doll is made up of large black and white photographs staged and taken by the author using an actual doll and teddy bears. There are people who are frightened of dolls, and although I am not one of them, I imagine that the reason is that they strongly resemble the human, but are not human; which is to say that they look real, and alive, whilst being of course not real and not alive. They cannot move spontaneously and they have a fixed facial expression; and yet, at the same time, they can be manipulated and made to be anything you want them to be. In Yasunari Kawabata’s House of the Sleeping Beauties the old men wanted to be with the sleeping women precisely because they had these doll-like qualities.

In this way, presuming that Dare Wright did want to create something touching and magical, the doll was a strange choice. Firstly, one is always aware that the author, the photographer, had to put Edith in those positions; one cannot look at the pictures without imagining an adult playing with a doll; or even, if you are able to believe in Edith, without seeing her as being somewhat in bondage to Wright. Secondly, because of her fixed expression, Edith cannot convey a range of emotions; and the expression that she does have is, with her sideways glance, one of unease. This works in the early stages, when she is alone, but becomes disquieting when Wright puts her in situations where she is meant to be mischievous or having fun, such as when she is at the beach or trying on adult clothes and make up. The same problem applies to the bears. The bigger bear, Mr. Bear, always looks angry, and the smaller one, Little Bear, looks positively despairing.

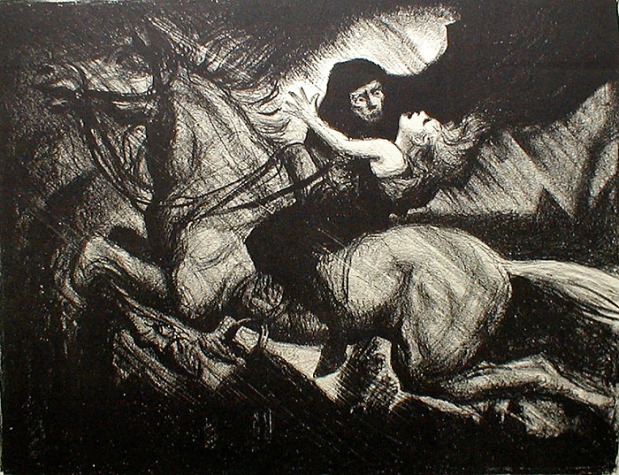

There is one, almost now infamous, photograph in The Lonely Doll, which shows Edith being spanked by Mr. Bear for being naughty. It is this photograph that readers tend to [or claim to] find the most disturbing; and to some extent I can understand that, although I feel as though it has more to do with a kind of prurience than anything else. Certainly, for me there are other images that are much more problematic. For example, on one page, when the bears first arrive, Little Bear whispers to the doll that she should see what kind of fun they are going to have. This alone is a little menacing, but the accompanying image – which can be found further up this page – shows her with her arms outspread and the two bears – one on each arm – giving the impression of holding her down. When the idea of having fun is later referenced again the photograph shows the doll running away from the bears. It does not, on any level, look like fun. Indeed, in this context her unease seems more like outright fear.

I would guess that the photographs are black and white because it was cheaper to reproduce them, but this too lends a kind of gloomy air to every image. However, not all of the weirdness is confined to the images and the author’s choice of toys. For example, when the bears arrive Mr. Bear calls Edith by her name, and nothing is ever said about how he knew it. After the introductions, they then simply move in. Where did they come from? Why is Mr. Bear, who one can only assume is an adult, moving in with a child? Why, for that matter, is the child living alone in the first place? What, finally, is the relationship between the two bears? Little Bear [is he a child? or just a small bear?] calls the larger bear Mr. Bear, not dad or father, or uncle or anything of that sort, which suggests that they are not related. In short, on every level, on every page, visually and within the story itself, The Lonely Doll is baffling, peculiar, and disconcerting.