Until recently I didn’t think that I was boring in bed. Or that I lacked imagination and a willingness to experiment. I have my preferences, yes, but I liked to believe that I was fairly open minded. However, when I started speaking to more and more people about sex, women mostly, I was shocked to discover that many acts that were not on my sexual radar [although I was aware of them, of course] were common fantasies and, it seems, were regularly being performed. Slapping and choking, for example. Oh, and fuck machines. ‘I want you to strap me into a dildo machine and watch as it fucks me.’ Seriously? I have to buy a machine now? Where does one get such a thing? And where on earth do we go after that? If this is the opening bid, so to speak, what exactly are we working up to here? Clearly, I had misjudged myself for many years. I am an amateur. A dabbler. Slipping between the sheets with me is like being asked to eat a raw potato.

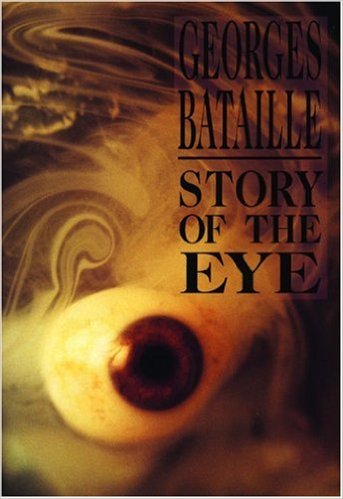

On this basis, one might imagine that Georges Bataille’s Story of the Eye – which, amongst other things, features gallons of piss, a fair amount of necrophilia, and the insertion of a human eyeball into a teenage girl’s anus – would not particularly appeal to me. Yet I have read it twice now; and, while almost all of the erotic content is at odds with my own desires, I could not have enjoyed it more. Indeed, I found it so engrossing the second time around that, against my better judgement, I took the book to work with me, so that I could continue reading it during my breaks. Thankfully, none of my colleagues felt compelled to ask me what exactly it was about the thin volume in my hands that inspired such a gleeful expression on my face. Had they done so I was prepared to lie, of course. It’s about an eye, ok? Now fuck off, and leave me in peace. Which, now I come to think about it, wouldn’t have been lie at all. It is about an eye.

Putting that eye business aside for a while, the book charts the relationship between the unnamed narrator and Simone, with each chapter focussing on one of their outré sexual escapades. It is, I believe, necessary to highlight the age of the couple. They are teenagers, young teenagers, being fifteen approaching sixteen when the novel begins. They are not adults, nor even close to being adults, and there is a definite sense of immaturity and playfulness, even innocence, about much of what they engage in. For example, the scene in which Simone cools her genitals in a saucer of milk, while punning upon the word ‘pussy’, is almost charming in its juvenile silliness. Moreover, this sort of thing isn’t confined to sex. The pair embark on a number of childish adventures, including trying to free one of their friends – Marcelle – from a sanatorium using a nail file.

So, on one level one could understand the book as being about adolescence, the discovery of one’s own body and the bodies of others, teenage sexual awakening, and so on. Indeed, there is a definite distinction drawn between the attitudes and behaviours of the youngsters and that of adults. When, for example, the narrator and Simone, and a group of their friends, stage an orgy it is broken up by their parents, who, as one would expect, react with dismay, with ‘desperate shrieks’ and ‘exaggerated threats.’ It is telling, moreover, that the children – with the exception of the central couple – break down, begin ‘howling and sobbing in a delirium of tearful screams.’ The adults in the book are at times the enemy – in one scene an unidentified figure literally pulls Marcelle away from a window while she masturbates – intent on spoiling their enjoyment or are figures of fun. On this latter point, consider how Simone’s timid mother is accidentally pissed on by her daughter, and how a priest is mocked, then murdered.

Yet I think there is more to Story of the Eye than an exploration of the generational gap. The narrator and Simone do certainly reject the adult world, but what is most significant about this is what that world represents, which is ‘normality’ and the conventional. Throughout the novel, the couple are intent on pushing the boundaries, on taking ‘any opportunity to indulge in unusual acts.’ Indeed, one of the most revealing moments is when the narrator attempts to take Simone in her bed and she refuses, because she does not want to be fucked ‘like a housewife or mother.’ Moreover, until close to the end of the novel Simone remains a vaginal virgin; prior to this point, and after it in truth, much of the couple’s sexual activity involves eggs, piss, come facials, and public – mutual and solo – masturbation.

There is, therefore, a deliberate avoidance of what might be considered normal or conventional sex. One gets the sense that pleasure is not the true aim, or that it is but that the pleasure is derived not directly from the flesh but from the extent to which these acts would be considered unnatural or inappropriate. It is interesting, in this regard, that there is only one moment, that I can recall, where the narrator is made to feel uncomfortable, when he refuses to allow or participate in an act, suggesting of course that he believes it would be ‘going too far.’ This is when Simone wants to sit on the testicles of a freshly killed bull while in public. One has to wonder why this particular act was deemed unacceptable by him, but helping a girl to fuck a dead priest, and to fuck her himself while she has the priest’s eye up her ass, is fair game.

“In general, people savor the “pleasures of the flesh” only on condition that they be insipid. But as of then, no doubt existed for me: I did not care for what is known as “pleasures of the flesh” because they really are insipid; I cared only for what is classified as “dirty.” On the other hand, I was not even satisfied with the usual debauchery, because the only thing it dirties is debauchery itself, while, in some way or other, anything sublime and perfectly pure is left intact by it.”

With this in mind, perhaps the most important character is Marcelle; certainly she is most important to the narrator and Simone, dominating their thoughts and playing a central role in their relationship. She has, we’re told, a ‘childlike simplicity’; she is shy and reluctant to get involved in her friend’s debauched behaviour. Indeed, her introduction into the novel involves them overpowering and raping her. She is, therefore, obviously representative of purity or innocence. This is made especially clear by virtue of her blonde hair, her white underwear [in contrast to Simone’s black], and the way that she is locked up in a sanatorium like a kind of fairytale princess in her tower.

However, she also represents repression and ‘naive’ piety. When, for example, she finds herself becoming turned on during the aforementioned orgy, she hides in a wardrobe in order to masturbate in private. Upon her ‘release’ [in both senses of the word] she imagines that the narrator is a Cardinal. Guilt, shame, and the way that the Catholic religion indoctrinates its followers into feeling these emotions, are all targets of disdain for the couple. Therefore, the death of the priest at the end of the novel is explained, I believe, in relation to Marcelle. He is, one might argue, killed for her. This interpretation is given greater authority when, after desecrating the church – both by copulating in there and by disposing of Don Aminado – the narrator sees Marcelle inside Simone’s vagina ‘gazing at me through tears of urine.’

I hinted towards the beginning of this review that I would return to the eye. It is necessary, of course. The novel is called Story of the Eye after all. Yet I am not sure how to fully account for its prominence, both for Bataille and in the most shocking act the couple perform, although there are certain ideas that suggest themselves to me. The eye is said to be a window to the soul, for example, and this is a book that concerns itself, as noted, with morality and religion. The eye could also be said to be the instrument by which we judge others, and it is perhaps significant, therefore, that Simone has one shoved up her ass. What is clear, in any case, is that, as with much that we encounter, it has a sexual-symbolic function. It is round and white, like a testicle, like an egg. All of these objects are connected in the mind of the author and in those of the teenage couple. You see the same thing with piss, milk, sperm, rain. The narrator himself describes the Milky Way as ‘astral sperm’; and a bullfight as like coitus. The purpose of this is, I’d argue, to emphasise that bodily fluids, smells, tastes, etc are natural, as natural as a thunderstorm, for example; and that, for such an obscene book, is a positive, liberating message.