‘You don’t ever talk to your friends about it?’ she asked. No, I replied, of course not. She – my partner at the time – laughed and said: you’re repressed. ‘We all go to the toilet; even girls, you know.’ Girls shit. I knew. I know. But did that mean it had to be a topic of conversation between us? Was I, in refusing to entertain the subject, denying her the level of intimacy that she deserved? Does every other couple comfortably share their excretory experiences? Maybe she was right: I am repressed. I don’t want to discuss bodily functions. Repressed, and probably a bad man. I remember someone once telling me about how her boyfriend would enter the bathroom and take a shit while she showered. Cool as you like. How often did this happen? Regularly, she said. Ah, I shouted, he waits until you are in the shower! He wants you to see and hear him shit, the dirty bastard! He wasn’t repressed. Certainly not. What a beautiful relationship they must have had.

“The only thing in the world that matters is us. Nobody will ever guess at the sublimities hidden within our hearts. Nobody else here on earth eats the brains from corpses and drinks the spittle of asthmatics. Let us act so that we might die in the satisfaction of having experienced, we alone, the True Sensation, of That Which Does Not Die.”

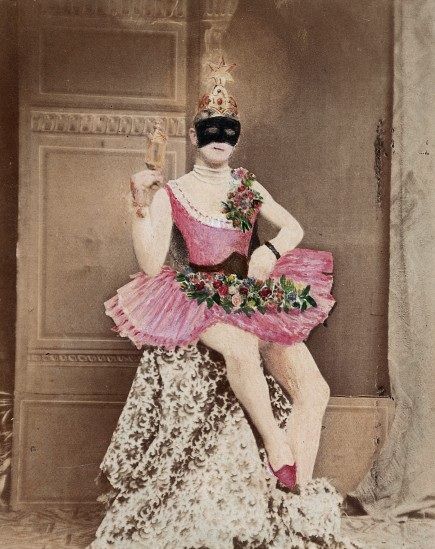

On the cover of the handsome Atlas Press edition of The Tutu it is stated that ‘it was written under the pseudonym of Princess Sappho, and is presumed to be the work of Leon Genonceaux.’ I do not often read the pages that precede a novel, but that ‘presumed’ tempted me, motivated me, to make one of my few exceptions via-a-vis Iain White’s introduction. I won’t retell the whole story here – or as much of the story as is known – but it is worth picking out some choice titbits. Genonceaux was responsible for publishing both Lautreamont and Rimbaud, the latter resulting in legal action against him. Marvellously, instead of facing up to the charge, he apparently went on the run. Later, he was charged again, on the grounds of publishing a book with an obscene cover, and again he fled. If someone is in fear of being arrested, is essentially in hiding, then putting one’s name to another obscene work – for The Tutu would almost certainly have been considered obscene – would not have been the wisest move. Hence: Princess Sappho.

However, as satisfyingly Borgesian as that all is, there’s more: some believe the book to be a hoax. On the first page of his introduction White writes that ‘it was published in the autumn of 1891’, but that ‘nearly all of the print run seems to have disappeared.’ Yet, in his final sentence, he asks: ‘what effect would it have had if it had indeed appeared in 1891, when it was written?’ Now, it is perfectly possible that I am misunderstanding his use of the term ‘published.’ To me that means that it made its way into the hands of the public, or at least had the potential to, if any of them had seen fit to part with money for it. Can something be published and not appear? Did White make a mistake? Or are we – the readers – being played here? [If you have the answers to any of these questions, then please keep them to yourself, for I do not want to have to rewrite this review]. In any case, the confusion surrounding the book, and more importantly the sense of playfulness, is certainly in keeping with the contents.

The Tutu is largely concerned with Mauri de Noirof, a dandyish sort who ‘always dressed with studied elegance.’ On the opening page he picks up a brick and wonders whether it ‘had a soul’ or whether it was ‘troubled by the rain.’ One understands immediately that he is something of an eccentric, a dreamer, a man perhaps at odds with his milieu. Indeed, his mother later says that she adores him because he is ‘not in the least like other men.’ And it is true, he isn’t, yet maybe not in the way that one is thinking; which is to say that he’s not a shy and sensitive little pup. The key to his character is, I think, evident in his chief ailment, which is his forgetfulness. Mauri’s bad memory – he orders cabs and makes appointments with women and keeps them waiting for hours – suggests to me, not that he has a serious medical condition, or that he is depressed, but that he is bored. It is as though he almost sleepwalks through life, barely allowing its events to trouble his consciousness. He says of himself that he is scared of life, but that didn’t come through to me. Alongside his boredom, I saw disgust and dissatisfaction, and it is the combination of all these feelings that, in my opinion, prompt his, let’s say, stomach-churning indulgences.

Of these indulgences, the most scandalous is his sexual interest in his mother, which is, moreover, reciprocated. Indeed, the book ends with Mauri bending her over a coffin, an act that is described as ‘impure and hideous.’ If one is bored, dissatisfied, and disgusted, then one might look to enliven one’s existence by doing something extreme, and, in an attempt to upset others, those others who disgust you, something shocking. Incest is, of course, considered unacceptable by society at large; and Mauri understands this, for numerous times he laments the law that prevents him from marrying the woman who brought him into the world. It is, therefore, the extremity, and shocking nature, of the act that makes it appealing, more than the physical charms of his mother. Furthermore, this act is likely to not only shock the people who disgust Mauri, but it sets him apart from them in his own mind, for it is something that they would never do. It is his being capable of it that makes him superior to them.

Yet not all of the unpleasantness contained within The Tutu is attributable to Mauri. In fact, the scene most likely to make the reader gag is when a man eats the tail of a dead, maggot-infested, cat. There is also – if you would like a list, either as warning or recommendation – piss, snot eating, vomit, shit [ah maybe now you see where I was going with my introduction], a woman breastfeeding snakes and another who is, um, tongued by a corpse. All of this leads one to wonder about the author’s intention. Was he trying to poke his finger in the ribs of people like me, the unapologetically repressed? Was he saying that this is life – bodily functions, death, decomposition – and one should not turn one’s head away from it? Certainly, I think that was part of it. But I also believe that he, in grotesquely humorous ways, wanted to urge his reader to make the most of their time on earth, which, as Mauri’s mother says, ‘ought to be an extraordinary sensation.’ This making the most of life, this experiencing of extraordinary sensations, need not mean drinking sputum and eating brains, of course, but rather not allowing oneself to, well, sleepwalk through it.

There is much more that I would like to discuss, especially the satire, but this review is overlong already, and the satire is rather obvious. Princess Sappho, or Leon Genonceaux, took pains to aim arrows at all of society’s pillars: marriage, religion, parent/child relationships, etc. Before concluding, however, I want to return to the idea that The Tutu might be a hoax. This theory holds up somewhat not only because of the obscure origins, and publication history, of the book, but also because it strikes one as modern in its construction. There is, for example, something of the surrealists automatic writing about the way the bizarre scenes seamlessly merge, so that one is not always sure where Mauri is or who he is talking to. There are, moreover, passages from other sources, including Maldoror; there is a conversation with God, a dream sequence, a picture, and a score. What one is left with, as one turns the final page, is less a feeling of disgust, although that is there too, but more an admiration for the author’s own joie de vivre, for his enjoyment in his creation is evident throughout.